The inaugural year of the University of Austin, or UATX as it’s known, had been marked by the frenzy and occasional chaos that one might expect from a start-up aimed at disrupting American higher education. The audacious experiment — the construction of a new university ostensibly based on principles of free expression and academic freedom — had drawn the interest and participation of a star-studded cast of public intellectuals, academics and tycoons.

Even measured against this high bar, however, April 2, 2025, would be a memorable day.

The night before, the campus had hosted a dinner and conversation between the prominent conservative historian Niall Ferguson and Larry Summers, the former Harvard University president and Treasury secretary. Later, that evening, the billionaire entrepreneur Peter Thiel would deliver the first of a series of lectures on the Antichrist. People at UATX had grown accustomed to fast-paced action.

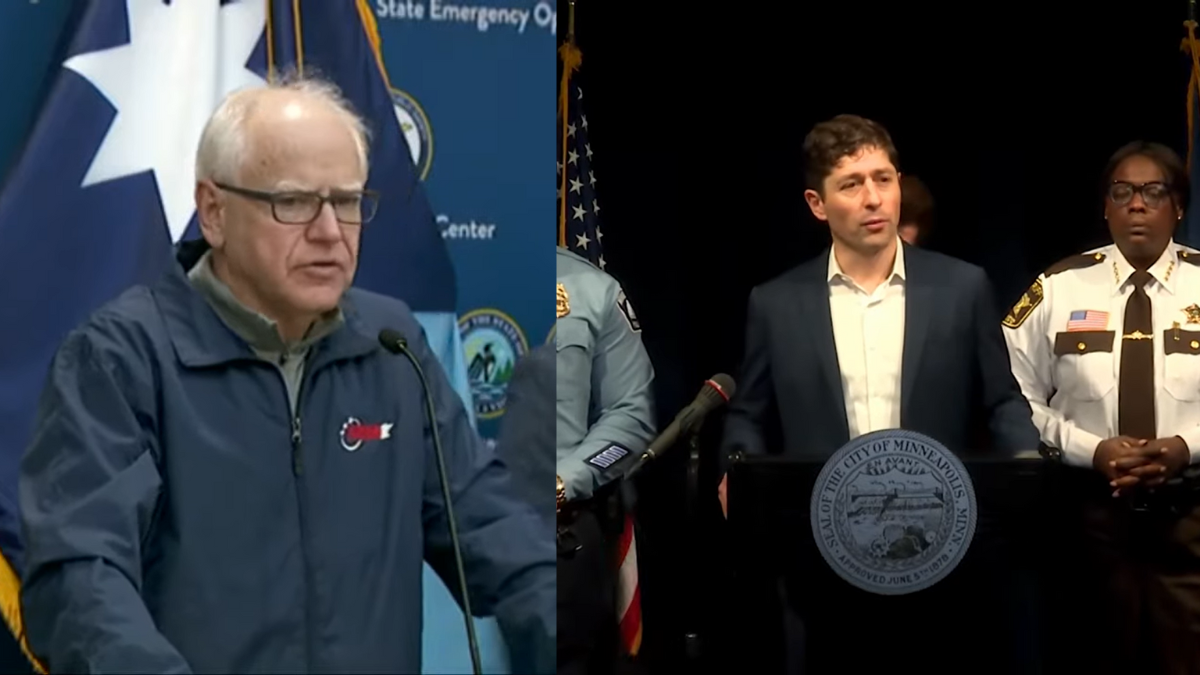

But in the afternoon, all of the professors and staff were summoned, quite unusually and mysteriously, to a closed-door meeting. It had been called by Joe Lonsdale, a billionaire entrepreneur who’d co-founded the data analytics company Palantir Technologies with Thiel. Together with Ferguson and the journalist Bari Weiss, Lonsdale had been a driving force behind the creation of UATX and was a member of the board of trustees. But he wasn’t often present on campus, and it was almost unheard of for a member of the board to summon the staff, as Lonsdale had.

The campus was quiet that Wednesday, the first of the spring term. The college, which operates under a quarter system, doesn’t schedule classes on Wednesdays, and so no students would be around to see the staff coming and going from the conference room in the elegant, former department store where UATX had made its home. Through the window, one could see the huge American flag in the atrium, illuminated by a skylight in the ceiling. It was a warm, pleasant day in Austin, but Lonsdale’s mood didn’t match the weather.

“Let’s get right into it,” he said. Then, with heightened affect, Lonsdale explained his vision for UATX — a jingoistic vision with shades of America First rhetoric that contrasted rather sharply with the image UATX had cultivated as a bastion of free speech and open inquiry.

“It was like a speech version of the ‘America love it or leave it’ bumper sticker,” one former staffer told me, and if you didn’t share the vision, the message was “there’s the door, you don’t belong here.” Like many of the people I spoke with for this story, the staffer was granted anonymity for fear of reprisal. “It was the most uncomfortable 35-to-40ish minutes I’ve ever experienced. People were shifting uncomfortably in their seats.”

The chancellor, Pano Kanelos, who’d recently been nominally promoted from the presidency, sat silently, noticeably ill at ease.

The harshness of Lonsdale’s diatribe would have been out of place on any college campus, but was particularly so at UATX, which had framed itself as a bulwark against the cancel culture that many contend has become common in the American academy. UATX’s image had never been entirely nonpartisan, but Lonsdale’s message signaled a decisive, rightward turn.

Michael Lind, a well-known writer and academic who’d co-founded the center-left think tank New America, bristled at Lonsdale’s remarks. After asking some probing questions, Lind announced his resignation as a visiting professor on the spot, dramatically depositing his key fob as he exited.

Not long after, in the nearby Driskill Hotel, Lind was in the midst of composing a letter of resignation when Ferguson called him and persuaded him to stay. In an email I obtained that was sent to Kanelos, the provost Jake Howland, the university dean Ben Crocker and a fellow professor, Morgan Marietta, Lind related what Ferguson had told him:

“According to Niall, under the constitution of UATX Joe Lonsdale, as chair of the board, had no authority to tell those of us at the meeting:

“That all staff and faculty of UATX must subscribe to the four principles of anti-communism, anti-socialism, identity politics, and anti-Islamism (this is the first time I heard of these four principles);

“That ‘communists’ have taken over many other universities and that he, Joe Lonsdale, would stay on the board for fifty years to make sure that no ‘communists’ took over UATX (the identity politics crowd and some Islamists are a threat, but the Marxist-Leninist menace in 2025?)”

Lind said when he asked for definitions of “communists” and “socialists,” he’d been toldthey included anybody who didn’t “believe in private property” and “hate the rich.” This, he wrote, struck him “as a libertarian political test excluding anyone to the left of Ayn Rand.” Lonsdale had said that the board would make a case-by-case determination on whether “New Deal liberals” would be allowed to work at UATX. Lind said that he considered himself “an heir to the New Deal liberal tradition of FDR, Truman, JFK and LBJ.” He was “in favor of dynamic capitalism in a mixed economy, moderately social democratic and pro-labor, and anti-progressive, anti-communist, and anti-identity politics.”

According to Lind, Londsdale repeatedly said that if the faculty weren’t comfortable with what he was saying they should quit.

“So I quit and I walked out,” Lind wrote.

But, Lind continued, “Niall emphasized that UATX is a real institution, not the plaything of donors and regents, and has a constitution that binds even the chairman of the board.”

Lind said that he took Ferguson at his word and withdrew his resignation on condition that “I am not Joe Lonsdale’s personal at-will employee, and that nobody at UATX needs to subscribe to the Four Principles of Joe Lonsdale Thought on penalty of losing his or her job.”

“I look forward to teaching my class tomorrow morning,” he concluded, adding that he would need a new key fob.

Neither Kanelos nor Lind responded to a request for comment. Lind’sbiography at New America does not mention an affiliation with UATX.

UATX did not make Lonsdale, Ferguson or Weiss available for comment and did not respond to a lengthy list of questions for this story. Lonsdale also did not respond to a request for comment sent to his venture capital firm 8VC.

The next morning, classes resumed, a seeming return to normalcy at UATX.

But, as the former staffer told me, “After that, everything was different.”

It’s a difference that should make a difference to anyone who cares about American higher education, free speech and academic freedom at a time when each faces unprecedented threats — both internal and external.

Because so many of its leaders lean conservative, UATX has been portrayed in some quarters as having been a right-wing project from the start. However, the truth is vastly more complex.

Over the past three months, I had more than 100 conversations with 25 current and former students, faculty and staffers at UATX. Each had their own perspective on the tumultuous events they shared with me, and some had personal grievances. But they were nearly unanimous in reporting that at its inception, UATX constituted a sincere effort to establish a transformative institution, uncompromisingly committed to the fundamental values of open inquiry and free expression.

They were nearly unanimous, too, in lamenting that it had failed to achieve this lofty goal and instead become something more conventional — an institution dominated by politics and ideology that was in many ways the conservative mirror image of the liberal academy it deplored. Almost everyone attributed significant weight to President Donald Trump’s return to power in emboldening right-leaning hardliners to aggressively assert their vision and reduce UATX from something potentially profound to something decidedly mundane.

It’s a tragedy worthy of the Greeks — whose view of classical education will soon take centerstage — which at its core is about the hubris of believing that first principles can transcend politics and the human temptation to succumb to power. In the staged version of the drama, the chorus would enter here to remind us that this essential flaw is one to which both the left and right fall prey.

UATX burst into the national consciousness on Nov. 8, 2021 with a coordinated media blitz. An article in The New York Times reported that a “a group of scholars and activists” had come together to build a new university “dedicated to free speech.”

The founders included Kanelos, who’d resigned the presidency of St. John’s College in Annapolis to run the new university, Weiss, Ferguson, Lonsdale and Heather Heying, an evolutionary biologist.

“Niall was the mind, Bari was the media and Joe was the money,” a former faculty member told me.

Binding the group was a sense of alarm over what UATX described on their website as “the illiberalism and censoriousness prevalent in America’s universities.” Weiss provided her Substack, “Common Sense” — later rebranded as The Free Press, to Kanelos to trumpet the birth of the school. “So much is broken in America,” he wrote. “But higher education might be the most fractured institution of all. There is a gaping chasm between the promise and the reality of higher education.” UATX was going to offer a new alternative. “An education rooted in the pursuit of truth,” he said, “is the antidote to the kind of ignorance and incivility that is everywhere around us.”

In a Bloomberg op-ed, Ferguson declared, “academic freedom dies in wokeness.” Lonsdale penned a piece for the New York Post, boldly promising that UATX would “prepare a new generation of leaders to think for themselves about all sides of an issue, speak truth to power, and take power back from ideologues.”

The announcement reverberated through the American academy; anyone who has spent time on a college campus over the past decade understands these concerns. In Heterodox Academy’s 2020 Campus Expression Survey, 62 percent of responding students said they believed their campus climate prevented students from saying things they believed. A 2024 survey, by FIRE, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, found that 35 percent of faculty self-censored or toned down their written work — about four times the rate reported by social scientists in 1954, at McCarthyism’s peak.

Kanelos said that universities had failed both students and the nation. Democracy was weakening because schools had become illiberal and incapable of producing citizens interested in or competent to participate in democratic governance. “We are done waiting for the legacy universities to right themselves,” he concluded in soaring rhetoric. “And so we are building anew.”

“I want to work there,” I told my wife.

Kanelos’ concerns resonated deeply with me, both intellectually and personally. I’m a lifelong civil libertarian and have watched with dismay as both the left and right have eroded academic freedom and open inquiry on college campuses. I’ve chronicled efforts to combat this trend for POLITICO Magazine. And, several years ago, I experienced a backlash firsthand, when a student excoriated me for defending the free speech rights of a conservative student at a campus forum on freedom of speech. With its lineup of heavy hitters, I thought UATX might be able to reverse the trend.

“I shared the same enthusiasm,” said Nadine Strossen, former president of the American Civil Liberties Union. “I was immediately enthusiastic about the mission of the university.” So too was Harvard linguist Steven Pinker. “I thought that alternative models of a university could enrich higher education and challenge the legacy universities to rethink entrenched practices,” he told me.

Kanelos identified 32 people as trustees, faculty members and advisers to the new university including Jonathan Haidt, the NYU professor whose work Kanelos evoked in proclaiming that UATX would produce an “antifragile” cohort with the capacity to think “fearlessly, nimbly, and inventively”; Summers; Pinker; the playwright David Mamet; Glenn Loury, an economist at Brown University; computer scientist and podcaster Lex Fridman; authors Andrew Sullivan and Rob Henderson; the journalists Caitlin Flanagan, Sohrab Ahmari and Jonathan Rauch; Stacy Hock, an investor and philanthropist; and Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a conservative, Dutch politician-turned-writer known for criticizing Islam’s treatment of women, and who is married to Ferguson.

The list leaned right, to be sure. Loury, who is Black, zealously opposes affirmative action. Mamet had called Trump “the best president since Abraham Lincoln.” Hock served as chairwoman of an organization called Texas GOP 2020 Victory. Several of the academics had experienced backlash for taking conservative positions. These included Dorian Abbot, a geophysicist who’d had a planned lecture at MIT on extraterrestrial life canceled over his views on DEI; Peter Boghossian, who’d resigned from Portland State University in part because of the institution’s response to his sending hoax articles to academic journals; and University of Sussex professor Kathleen Stock, who’d faced protests over her allegedly transphobic views, which she disputed.

But Summers had served in Bill Clinton’s Cabinet and as Barack Obama’s chief economic advisor. Others were unconventional, independent thinkers, and several, including Haidt and Strossen, had made advocating for free inquiry and open dialogue a major part of their life’s work. It was possible to believe that the group had just enough viewpoint diversity, and a depth of commitment to civil libertarian principles, that it might transcend the virtue signaling, intellectual hegemony and inclination to cancel that had stalled many American colleges and universities.

The coming together of this unlikely coalition sparked widespread enthusiasm. “It was the easiest fundraising pitch ever — a very American project in the best way,” the former staffer told me. “I never had an easier time getting meetings with wealthy people.” UATX stated an ambitious goal of raising $250 million. Just eighteen months later, they reported being more than halfway there.

But the early successes masked significant, underlying conflicts. While the university leadership was largely united in the need to respond to cancel culture, there was no consensus around an affirmative vision for the university.

The core problem was simple but profound: It was clear what UATX was not but entirely unclear what it was.

It took only a week for the simmering conflicts to bubble into the public eye. On Nov. 15, 2021, Pinker announced on social media that he would be stepping off the board of advisers by “mutual & amicable agreement.” The same day, University of Chicago Chancellor Robert Zimmer announced that he’d resigned from the board four days earlier.

Zimmer’s resignation hinted at one of the fault lines: how much UATX would be defined by what it was against and how strongly it would make its negative case against the elite colleges it viewed as its competition. Several people I interviewed said that Lonsdale in particular was highly motivated to vanquish such rivals, including his alma mater Stanford University.

Indeed, some early statements had a bit of throwing-down-the-gauntlet vibe. Of administrators and professors who felt threatened by UATX’s disruption of the system, Kanelos said, “We welcome their opprobrium and will regard it as vindication.” Ferguson wrote that he’d taught at Cambridge, Oxford, New York University and Harvard and had come “to doubt that the existing universities can be swiftly cured of their current pathologies.” He’d later refer to UATX as “the anti-Harvard.”

The early resignations seemed to be in response to the aggressiveness of the negative rhetoric. “The new university made a number of statements about higher education in general, largely quite critical, that diverged very significantly from my own views,” wrote Zimmer, who died in 2023.

“Dissociation was the only choice,” Pinker told me in an email. “I bristled at their Trump-Musk-style of trolling, taunting, and demonizing, without the maturity and dignity that ought to accompany a major rethinking of higher education.” Furthermore, Pinker added, “UATX had no coherent vision of what higher education in the 21st century ought to be. Instead, they created UnWoke U led by a Faculty of the Canceled.”

Other departures followed. University of Chicago law professor Geoffrey Stone left the advisory board in October, telling Fortune that participation with UATX wasn’t a good fit since he believed universities should be non-ideological. In an email, Stone told me, “I had no time to be involved, so I resigned.” Photos of Tufts political science professor Vickie Sullivan and journalist Lex Fridman were removed from the website, as was mention of the journalist Andrew Sullivan and University of Sussex professor Kathleen Stock. Neither Fridman nor Vickie Sullivan nor Stock responded to requests for comment. In an email, Andrew Sullivan wrote, “I just didn’t have the time or energy to do it justice.”

On Dec. 2, 2022, Heying resigned from the board, saying that it was “better to separate myself from the University, than to have my name be attached to an institution that does not represent my scientific and pedagogical values.” In a letter published on her Substack, “Natural Selections,” Heying wrote that she didn’t think her colleagues’ vision was “sufficiently revolutionary.” To fix higher ed, UATX needed to address the root causes of “academic fragility,” which she argued, would require “tolerance for a great deal more risk than I think there is appetite for in this group.” Except for their reservations about DEI and cancel culture, Heying wrote, “It seems that others on the Board have trust in existing elite institutions.”

Indeed, for a college committed to disrupting the status quo, UATX would come to rely quite heavily on traditional markers of merit for admissions. Today, UATX guarantees admission to anyone scoring at least a 1460 on the SAT, a 33 on the ACT or a 105 on the CLT. According to a UATX Substack, applicants below that threshold are evaluated on the basis of test scores, results on advanced placement and international baccalaureate exams, and three verifiable achievements, “each described in a single sentence.”

“There was no thinking expansively about whom to admit,” Heying told me. “This was just going to be another elite institution — anti-woke Stanford 2.0.”

Almost everyone I interviewed shared Pinker’s view that UATX lacked a unifying, coherent vision in its early days. But that’s not to say that individual leaders didn’t have their own, coherent visions. Soon, factions began to emerge.

In one corner was Kanelos and his supporters. While Kanelos had engaged in some challenging banter with the establishment, he’d also staked out some high ground. “We wanted to be able to bring together students and faculty from across ideological boundaries and throw in front of them some of the most vexing questions of the day,” Kanelos said in a 2022 interview. “Questions around empire, or gender, or race, and create a circle of trust where these students and faculty, who differ in so many ways, find what I call the highest common denominator.” Kanelos also emphasized UATX’s intellectual diversity. “Our backgrounds and experiences are diverse,”he wrote. “Our political views differ.” Heying echoed the sentiment. “The people who started Austin were not the alt right,” she told me.

“Pano is a decent, honorable person,” Heying said, echoing a view I heard from many others. She recalled having conversations with Kanelos about alternate pedagogies and ways to build something “not just like all of the other elite institutions out there.” But, she said, “those conversations withered on the vine.”

A faction competing with Kanelos’ included Lonsdale and several of his allies. Their view is difficult to categorize, and no two people described the lines of division the same way. Some framed it as a battle between the conservatives and the libertarians. Others saw it as the classicists versus the tech bros. But one name came up far more often than any other: Leo Strauss.

A German-Jewish emigrant, Strauss spent most of his career at the University of Chicago. An impactful teacher and prolific writer, Straus criticized modern liberalism for undermining the influence of religion and natural law and advocated a return to teaching the ancient Greeks, who he said had deep insights into human nature and society.

Strauss isn’t a household name, but he’s deeply influential on the modern right.

One can draw a straight line from Strauss to his student Allan Bloom, author of the 1987 bestseller, The Closing of the American Mind, which sounded an early alarm against identity politics, moral relativism and the decay of the university. From there one can make a direct connection to the prominent conservative intellectual Patrick Deneen, who has argued that liberalism’s emphasis on individual rights degrades authority, community and place. Deneen, who reportedly modeled himself on Bloom, won the American Political Science Association’s Leo Strauss Award in 1995 for best dissertation in political theory. Strauss was also the subject of a symposium at UATX in early January 2026, hosted by Loren Rotner, who received his PhD from Claremont Graduate University — a key institution for fueling what was known as West Coast Straussianism.

Kanelos’ view of the academy emphasized pluralism and the individual’s search for truth. On the other side, the Straussians weren’t quite so agnostic. They had a view of the common good they wanted to assert.

This conflict came to a head for the first time in September 2023 when Rotner, then the assistant provost, and Hillel Ofek, then the vice president of communications, engaged in what was described to me by several people as “a coup attempt.” They were critical of Kanelos’ leadership and believed that UATX had been neither aggressive enough in criticizing the universities with which they were in competition nor establishing UATX’s own identity. Another former staffer, who was granted anonymity out of fear of retaliation, said, “They attempted to persuade the UATX board that everything was heading in the wrong direction.”

The rebellion failed. Ofek and Rotner left UATX. Ofek took a position as director of strategy at Lonsdale Enterprises. Rotner became director of the Cosmos Institute, a nonprofit aimed at using AI for human flourishing. UATX did not make Rotner and Ofek, who have since returned to UATX as associate provost and chief strategy officer respectively, available for interviews or to provide comments.

Kanelos survived. UATX moved forward and began recruiting its first class.

In May, 2024, they hit a bump in the road when Jonathan Yudelman, a recent hire from Arizona State University, confronted a woman in a hijab in a video that went viral. But Yudelman was mostly associated with ASU, rather than UATX. The incident was handled internally and soon blew over. Yudelman remains at the university. UATX did not offer a comment on the episode, and Yudelman did not respond to a request for comment.

On Sept. 2, 2024, UATX opened its doors, presenting a united front to the world. In the morning, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott met with the inaugural class of 92 students at the state capitol. Down the block, in the Capital Ballroom of the Royal Sonesta Hotel, the students donned dark blue robes, signed the University of Austin register and, in return, received a copy of The Odyssey. Kanelos, clad in regalia, delivered a rousing address.

“History is not a story unfolding; it is an epic being written. And its authors are those bold enough to exercise their agency in the pursuit of higher things,” he said. According to Kanelos, UATX was returning to the Platonic ideal — to the “olive grove on the fringes of Athens called the Akademia,” where students came together to ask “fundamental human questions.”

There were other schools in Greece, but Kanelos said Plato’s stood above them all. “What distinguished Plato’s Academy,” he told the students, “was doctrinal pluralism and a variety of intellectual approaches. There were no easy answers. Every discussion branched outward with ever-greater complexity.”

The pluralists had won. At least for the moment.

In a truth-is-stranger-than-fiction turn of events, UATX’s commitment to its founding principles would be tested on the school’s first day of operation by an incident of alleged sexual harassment that would dominate the campus’ freshman year.

The anti-woke founders of UATX hated every aspect of cancel culture, but they had a particular, visceral enmity for the procedures surrounding the adjudication of sexual misconduct allegations under Title IX.

In December 2023, Ferguson published a manifesto of sorts in The Free Press — the “Treason of the Intellectuals.” Over his long career, Ferguson wrote, he’d witnessed “the politicization of American universities by an illiberal coalition of ‘woke’ progressives, adherents of ‘critical race theory,’ and apologists for Islamist extremism.” Still, he reserved some of his harshest language for the “armies of DEI and Title IX officers,” who, he said, seemed, at many colleges, to outnumber the students. Because these universities are rich, Ferguson said in an interview shortly after the article’s publication, “they’re allowed to grow these enormous bureaucracies of non-academics, people not engaged in research or in teaching, purely engaged in administration. They’re a huge part of the problem.”

Again, many, many people in academia would concede that Ferguson and his colleagues were onto something. In 2014, a group of 28 current and former Harvard Law School professors published a letter in the Boston Globe arguing that the university’s procedures for deciding sexual misconduct claims lacked basic due process and were stacked against the accused. In 2024, FIRE excoriated new regulations from the Biden administration which, among other things, eliminated an accused’s right to a live hearing, threw out their right to cross-examine their accuser and witnesses, and allowed a single administrator to act as prosecutor, judge and jury.

UATX didn’t plan on accepting federal funding and hence wouldn’t be strictly constrained by Title IX. So, they were free to innovate. They took the novel step of drafting a constitution, which created a system of checks and balances. The Board of Trustees acted as the legislative branch, the president as the executive, and an external adjudicative panel as the judicial branch, with the power to enforce a bill of rights that protected academic freedom and other student and faculty rights.

Morgan Marietta, a former professor, credited Ferguson for developing this innovative structure. “This vision of constitutionalism, once you hear it, you realize, oh, that’s it,” he told me. “That is the great American idea that we should have realized should have been governing universities for the last 200 years. It should all be honest and open and transparent.”

But a theoretical commitment to constitutionalism was one thing. Its practical application to a sharply disputed campus incident was quite another.

For UATX’s inaugural freshman class, the first week of September 2024, was — in the words of a current student — “insane and fully booked.” They met donors, went on hikes, pitched businesses, had a pool party at Lonsdale’s house and read The Odyssey — with 60 Minutes filming many of the proceedings for a segment that would air in November.

The new students were a tightly knit group. Everyone lived in two floors of the Union on 24th, an apartment building, and took a private shuttle to cover the two miles to the Scarborough Building, the former department store where the college made its home. Most people didn’t think much of it when the university dean, Ben Crocker, called a student named Dan into his office on Monday, Sept. 9, the first day of classes. But at 7:44 in the evening, they received an email from three administrators saying that Dan had been removed from campus, “transported to his home out of state,” and barred from further access to the university.

(Dan is a pseudonym. POLITICO has granted him anonymity so he would speak candidly about the situation and about allegations that have not been proven in a court of law.)

The nature of the allegations concerned, at their core, a pair of charged statements Dan allegedly made that would be familiar to any Title IX officer. The first was a general statement implying that UATX girls carried themselves physically in a way that invited sexual assault. The second was a suggestion to a specific female student that she had carried herself in a way that invited sexual assault. Dan had already been the subject of some negative attention on campus because of provocative statements he’d made in a UATX-based Discord “introductions” chat. These included a challenge — “If I catch any of you guys in my stuff, I’ll kill you” — which was a reference to the 1981 movie “Stripes” and likely misunderstood by fellow students. In another exchange, a discussion of transgender issues, Dan expressed reservations about hormone treatment and said that he couldn’t wait “to play devil’s advocate for legalizing pedophilia.”

Between 8:30 and 9:00 p.m., Crocker visited the dorms, where he hosted a meeting on the roof to discuss the issue with students. Crocker’s message was that Dan’s conduct had been evaluated to be a “credible threat” — a phrase that would be repeated by the administration many times over the following days. Crocker then faced what one student attendee recalled as a “firing squad” of questions. Some students said that Dan had seemed off, but others saw his hasty removal as an example of the very cancel culture to which UATX was supposed to be the antithesis.

The following day, at lunch, Kanelos addressed the student body. He explained that he’d had to make calls in his career as a university president about how to protect students, that he took his commitment to student safety seriously, and that, in his view, the extraordinary circumstances called for Dan’s temporary removal. Students asked whether Dan would be appointed a lawyer and granted a hearing. “We were told, ‘yes and yes,’” said one student who attended the presentation.

I have spoken multiple times with Dan, who adamantly denies the allegations and says that he was appointed a faculty advocate but not a lawyer. Several students with whom I spoke and who were present at the gathering said that Dan had never directed a comment at a specific student.

“I’ll swear on the Bible that it didn’t happen,” said one student who, like several other students, was granted anonymity for fear of reprisal from the university.

McKenna Conlin, a current UATX student and former resident advisor, told investigators that Dan hadn’t said what he’d been accused of saying and that the affair had been a misunderstanding. She, Dan and others had been discussing the Title IX training that UATX had provided to the resident advisors, which was viewed as outdated and ineffective. They’d joked that better training might have prevented some inappropriate comments they’d heard from other male students — including the offensive comment Dan was accused of making. The comments on Discord had also been misunderstood, Conlin and others said, and were better understood as the product of an apparently neurodivergent mind embracing the college’s pro-speech mission than as sinister.

The student who allegedly issued the complaint did not respond to an email from POLITICO Magazine.

In any event, what divided the campus was not so much the truth of the allegations as the speed and process by which they were decided. Dan told me that while the community was told that his suspension was temporary, he was told on the first day of class that he was being expelled.

“The first day was a huge gut punch,” said a former student. “A week before, we’d got grandiose speeches about how we were done with the Title IX bullshit, and they even spoke about, you know, what happened to Brett Kavanaugh was terrible. The entire culture just eroded in the blink of an eye.” The former student pointed to it as the principal cause of his decision to withdraw from UATX at the end of his freshman year.

Another former faculty member who was closely involved with Dan’s situation expressed similar disillusionment with the process. Indeed, when the UATX adjudicative panel — comprising outside legal experts — reviewed Dan’s expulsion, it found that the procedures had violated the school’s constitution in several regards by, among other things, depriving him of his right to a public hearing and failing to include students in the jury that reached an initial determination on the expulsion decision. UATX argued that these provisions violated Texas law. The university thus took the highly unusual position that its own constitution was illegal, but Dan didn’t challenge this, and so the panel accepted the university’s argument. However, the panel also found that Dan had been deprived of his right to obtain witnesses in his favor.

The adjudicative panel’s decision — which POLITICO Magazine has obtained — referred to the procedures surrounding Dan’s case as “shambolic,” and said that UATX’s counsel had said of the procedures that they’d been “building the plane while we’re flying it.” “It was cobbling together handbooks, policies, and procedures,” the decision quotes UATX’s lawyer as saying. “There were a lot of cooks in the kitchen. The judicial handbook from what I understand was coming together kind of as a live document for a long time.”

The panel ultimately recommended that the school’s constitution be revised to conform with Texas law and that Dan effectively be retried under the new procedure and with the right to call witnesses.

According to the former faculty member , the university disregarded the panel.

“It was like, ‘Lord give me constitutionalism, but not yet,’” the former faculty member said. “It’s too bad. It would have been glorious.” Many faulted Kanelos for the departure from UATX’s founding charter.

UATX did not respond to a request for comment about the matter and did not make Crocker available for comment.

Dan confirms that a rehearing that might have allowed him to clear his name was never scheduled. He was, however, offered to reenroll at UATX, though with neither a guarantee of continued financial aid nor clarity as to the specifics of how to manage a return that would be “clearly uncomfortable for everybody,” and he ultimately did not return. (Tuition at UATX is free, but students bear the costs of housing, food and textbooks.)

Nearly ten months passed between the incident and when the adjudicative panel reached its decision in June 2025. It lingered so long that most students viewed it as the defining issue of their freshman year.

“The mood was strange, and I can’t honestly say it ever became normal,” said Conlin. “For many of us, there was immediate and irreparable damage of trust with university administrators that has stayed to this day.”

With Dan’s case lingering in the background, UATX students settled into college life, which most students with whom I spoke found — Kanelos’ claims of revolutionary disruption notwithstanding — to be similar in many regards to any other campus.

UATX did not grant my request to visit, and classes operate under the Chatham House Rule, which prevents students from identifying speakers in the classroom — a prohibition respected by every student with whom I spoke. But several students had previously pursued degrees or taken classes at other colleges and thus had relevant points of reference. They said many campus dynamics would be familiar at any college — students ate together, dated their classmates and worried about exams. At the same time, several differences stood out.

The first is that UATX is not yet accredited (and under Texas law cannot call itself a college). It operates under a Certificate of Authority, awarded by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, on which Hock serves as chair. UATX is seeking accreditation from the Middle States Commission on Higher Education. Generally speaking, a college must graduate at least one class as a prerequisite for accreditation. UATX’s first class is scheduled to graduate in 2028.

Several students noted a lack of diversity. Consistent with its emphasis on “merit-based admissions,” UATX doesn’t publish demographic data. The students with whom I spoke said their classmates — and the college’s leadership — were overwhelmingly white, disproportionately came from wealthy families and had an overrepresentation of apparent neurodivergence. They found ideological diversity to be particularly lacking. “I didn’t realize exactly how conservative it would be,” one current student told me. “You know, when I hear free speech and open debate and all that jazz, I assumed that there was going to be a more equal amount of political views, and there wasn’t.”

Classes weren’t as innovative as most students expected. “Year one was exceptionally boring,” the student said. “They did great books, they just didn’t do it in a great way,” said another student, who lamented the amount of memorization required. “I thought we were going to be intensely debating,” he said.

Several students shared course syllabi with me. Most are easy enough to imagine being offered on any campus — with the notable exception of math and science. “The math classes go over algebra you learned in ninth grade,” a student told me. “There was just nothing there.” He described the offering as “schizophrenic” and described a class he’d taken at University of Texas at Austin as “exponentially more important.”

Indeed, the syllabus I reviewed for a class called “Intellectual Foundations of Science II” covered a range of topics unusual for a science class including “The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief.” A student who’d taken the course shared a slide with me on “ensoulment” — the principally religious question of when a soul enters the human body — and said that the class had been told that IVF but not abortion could be consistent with the Catholic belief about ensoulment.

The poor quality of the science offerings had bothered Heying and Pinker. “Others thought I was the token liberal,” Heying told me, “but I came to understand myself as the token scientist.” In an email, Pinker wrote, “They should have hired a widely esteemed scientist and proven program builder to set up their science division.”

Another surprising similarity with other colleges stemmed directly from Dan’s expulsion: The students feared cancellation. “At any moment a frivolous Title IX complaint could be filed against you,” Fred told me. “I’ve never felt my speech was so chilled as it was in the classroom at UATX.”

As UATX’s first semester ended and Trump reascended, the pluralists began to lose their grip on power.

In December 2024, Ferguson attended a fundraiser at Mar-a-Lago hosted by Marissa Streit, CEO of the conservative educational nonprofit PragerU, which, among other things, has produced material comparing climate change deniers to Jews who resisted the Nazis. Soon thereafter, Ferguson softened his previously harsh criticisms of Trump, saying that he’d been wrong to call him a “would-be tyrant,” that the system could contain whatever tyrannical impulses the once-and-future president might have, and that it would have been a “disaster” if Kamala Harris had won the election.

In January 2025, UATX experienced its second attempted coup in less than a year and a half. “A consortium led by Lonsdale convinced the board that everything was going in the wrong direction,” a former senior staffer told me. They argued that “our great books curriculum was misguided, we weren’t doing enough on tech and our founding president was the wrong person for the job.”

This time Kanelos wouldn’t escape unscathed. On Jan. 10, Ferguson and Lonsdale announced that Kanelos had “graciously accepted” an offer to be “elevated” to the newly created role of chancellor, modeled on Oxford University. Other major changes would follow.

In March, Ofek and Rotner, who’d been principal architects of the first failed coup, returned.

Around the same time, UATX ended its relationship with Ellie Avishai and The Mill Institute, a nonprofit she led dedicated to promoting viewpoint diversity, which Kanelos had housed at UATX and supported with a half million dollar advance against future fundraising. Avishai’s sin appeared to be reposting on her LinkedIn account an article by the psychologist Michael Strambler, which argued that DEI was neither all good nor all bad. More deeply, the article condemned the temptation of embracing absolutist positions. Strambler gave a shout out to The Mill Institute, whose slogan is “Less certain, more curious.” The post attracted little attention — only 19 reactions — but two days later, Avishai was ousted unceremoniously. “The only communication that I personally received from the university was a phone call from this junior guy who was sort of happy to be the hammer,” Avishai told me.

The shifts in personnel coincided with shifts in advertising and admissions. “Come to a school that doesn’t hate you” read an ad in The New Criterion, a conservative literary magazine — which several people told me was intended as a reference to reports of antisemitism on other college campuses. Some of UATX’s early rhetoric had been challenging, but it hadn’t been in print and it hadn’t been this direct.

“Once we started going negative, gifts started drying up,” said the same senior former staffer, though, in retrospect, it might be more accurate to say that the diversity of the gifts started to shift. In November, UATX announced that it had received a $100 million gift from Jeffrey Yass, a billionaire investor who has been a significant supporter of Trump and MAGA-related causes.

On March 31, UATX announced its new “merit-first” admissions policy, guaranteeing admissions on the basis of standardized test scores.

Two days later, Lonsdale would address the all-staff meeting, and the extent to which things had changed would become apparent to everyone.

When UATX’s supporters and advisers came together for the college’s annual First Principles Summit — on May 3 — the rightward pivot away from pluralism couldn’t be ignored. The day before, the university had announced its new president: Carlos Carvalho, a professor of statistics at UT Austin’s McCombs School of Business, but it was Ferguson who held the spotlight.

Ferguson briefly addressed Kanelos’ change in role. “We shall soon have a constitutional monarch and a prime minister,” he said, according to a transcript of his remarks obtained by POLITICO Magazine. “I believe you will soon see the benefits of this modification to our constitutional order.” The bulk of his remarks focused on the Trump administration’s threats to the existing higher education order. The day after Lonsdale’s all-staff meeting, Harvard had received a letter accusing it of failing to protect students from antisemitism followed, one week later, by a letter demanding a long list of reforms as a condition of receiving continued federal funding.

In mid-April, FIRE issued a statement condemning the attacks as an infringement of the First Amendment and academic freedom that would “render Harvard a vassal institution.” At the summit, Ferguson said that UATX’s leaders needed to “think twice” before they uncritically embraced FIRE’s narrative that Trump was “the villain” and Harvard professors the heroes.

In the audience that day was Strossen, who in addition to serving as an adviser to UATX was a senior fellow at FIRE, a leading expert on First Amendment law and a past president of the ACLU. In advance of the meeting, Strossen had submitted questions about the separation from the Mill Institute and how well the university’s constitution was working.

But, Strossen said, none of her questions were on the agenda. “There was, in fact, no opportunity for meaningful input by members of the Board of Advisors,” she told me. “It was just a show-and-tell session, and it wasn’t even show-and-tell. It was like lecturing at us.”

Strossen said that she admired Ferguson — “he’s brilliant, he’s witty, he’s erudite” — but she strongly disagreed with his questioning how FIRE could defend Harvard. “It’s as absurd as saying, ‘How can the ACLU be defending the Nazis?’” she said. “There had never been a stronger critic of Harvard,” Strossen added, noting that FIRE had ranked Harvard at the bottom of its free-speech rankings. “We were defending the academic freedom principles that were threatened by what the Trump administration was doing.”

The next day, a Sunday, Strossen emailed several people including Kanelos, Ferguson, Rauch, and FIRE’s CEO Greg Lukianoff. “I believe it is critically important for UATX, with its signature mission of defending academic freedom principles, to weigh in as a defender of these principles in the current context,” she wrote in the email obtained by POLITICO Magazine. “Otherwise, UATX will subject itself to plausible criticism that it is less concerned about the neutral pursuit of truth/protection of academic freedom than about attacking existing universities and/or supporting the Trump Administration.”

Kanelos offered to sign onto a joint opinion piece with Strossen on the Trump administration’s actions, but no one else expressed support for the idea. Strossen had the sense that Kanelos would be speaking for himself rather than UATX, and nothing ever came of her email.

“When we were no longer aligned with FIRE and the Mill Institute, I knew that we were fucked,” Conlin said.

On May 16, Avishai published an account of her firing — titled “Is the University Of Austin Betraying Its Founding Principles?” in Quillette, an online journal focused on free speech and identity politics.

One day later, Ahmari, who said he’d been brought into the project by Weiss, announced his resignation on X — citing his concern with Avishai’s termination. “I don’t believe in a value-neutral university. I’m not a free speech absolutist,” Ahmari told me. “But nevertheless, I want a credible institution and an institution that is, because of its richer worldview, more reasonable.”

“When you fire an administrator or you put pressure on her, because she said, ‘Look, I don’t like institutional DEI, but I think we should uphold diversity as a value,’ which is a perfectly innocuous thing to say, and I think kind of right for a university context — that’s more unreasonable than some of the stuff that went on at the ‘woke’ university that these people critiqued.” Ahmari said.

“I just felt like the worldview that was being pushed was just kind of a very gruff, intolerant conservatism, and not even an elevated one,” he said, “and it was too beholden to the donors, especially Joe Lonsdale.”

Over the summer, UATX drifted further away from pluralism and toward a more rigid, hard-right orthodoxy.

On July 15, the conservative Manhattan Institute issued a statement calling on Trump to draft a new contract with universities, violations of which should be punishable by revocation of all public benefit. “Beginning with the George Floyd riots and culminating in the celebration of the Hamas terror campaign,” the statement read, “the institutions of higher education finally ripped off the mask and revealed their animating spirit: racialism, ideology, chaos.” Universities had become tyrannical agents of “the Left” and forgotten that they and the state were “bound together by compact.” The signatories included Ferguson, Ali, Boghossian, now a faculty advisor at UATX, and UATX professor Alex Priou.

Two days later, the new president, Carvalho, issued a response on the UATX Substack. “This crisis is why UATX was founded,” he wrote, noting that the Manhattan Institute statement had been endorsed by “countless others — including members and supporters of UATX.”

Carvalho’s response was the final straw for some advisers. “It was all but a full-throated endorsement of the Manhattan Institute statement,” said Strossen. “That was to me completely antithetical to academic freedom, which was supposedly the core mission of the University of Austin.”

In a last-ditch effort of sorts, Rauch, Haidt and Strossen organized a call with Carvalho. The discussion didn’t inspire confidence in the group, said someone with knowledge of the call who was granted anonymity to speak candidly. Carvalho basically told them that UATX was a right-wing project, and that they’d known this when they signed up. But that wasn’t what any of them had believed.

On July 18, Summersannounced his resignation from UATX on X. The former Harvard president said that he saw major problems with the lack of diverse perspectives in elite institutions, but was “not comfortable with the course that UATX has set nor the messages it promulgates.”

The next day, Strossen declared her intention to resign. “I have become increasingly uneasy with UATX’s apparent drifting away from its mission of offering an exemplary model to galvanize other universities to live up to their truth-seeking missions,” she wrote in an email to Carvalho, Ferguson, Kanelos and Howland. Instead, she saw it “drifting too much toward piling onto the revengeful “anti-Woke” bandwagon,” citing the firing of the Mill Institute personnel as one of several additional concerns.

Carvalho asked her to defer her resignation until early August. Strossen obliged and told me that she wanted to do the “least possible damage to the institution.” Haidt and Rauch quietly separated from UATX shortly thereafter. Neither responded to a request for comment.

Over the late spring and early summer, so many other resignations and terminations followed that it was difficult to keep up.

The head of fundraising, Chad Thevenot, announced his resignation immediately after the April all-staff meeting. By the end of the summer, according to one of his former senior staff members, about half of Thevenot’s staff of approximately 15 had followed suit. (Thevenot, who recently co-founded a start-up called The Athos Group with Kanelos, did not respond to a request for an interview. On LinkedIn, Thevenot described Athos as “a firm devoted to helping founders, funders, and leaders build and renew the institutions that sustain a free and flourishing society.”) Overall, the former senior staffer estimated that approximately a third of the school’s staff resigned over the spring and summer. Of the 32 supporters Kanelos identified in his original announcement, nearly half had departed by the end of the summer of 2025.

The original constitution did not provide for the firing of the provost, but it was amended in May to allow the president to fire the provost with consent of the trustees. About two months later, Howland, the widely-admired provost — one of the few remaining senior staffers loyal to Kanelos — left the college. Several people I spoke with indicated that he’d been fired. (Howland, who is also joining The Athos Group, did not respond to a request for comment.)

In July, the constitution was changed yet again, significantly expanding the president’s power. Under the new rules, the president had ultimate authority to appoint investigators and impose sanctions. There would be no more public hearings or impartial juries.

When students returned for the second year of operation, the consolidation of power was nearly complete.

During the many conversations I had reporting this story, two questions came up more than any other.

The first: Where was Bari Weiss? Many of the people I interviewed told me about internal conversations and shared internal emails. Weiss, who remains on the board of trustees, was almost never present in the conversations as they were related to me, and while I saw many emails on which Kanelos and Ferguson were copied, I never saw any including Weiss.

One person I spoke to, who was present during the early planning stages, told me that Weiss was “very elusive” and almost never present in person. This was ironic since UATX was closely associated with Weiss — a bust of whom now resides in the school library. Weiss, meanwhile, has only risen further during the Trump 2.0 era and is now editor-in-chief of CBS News, where she has been criticized as genuflecting to the Trump administration. A spokesperson for CBS News did not respond to a request for comment from Weiss.

One former member of the development team told me that they would routinely ask prospective donors how they got to know UATX. “Eighty percent of the time, the answer was Bari Weiss,” they said. “It was very often referred to as Bari Weiss’ University, or Bari Weiss’ University Project, or Bari Weiss’ University of Austin.”

For several people, this was a source of resentment. “I don’t care whether she wants to pretend this is all gone now — she is the reason that this place exists. She was huge, she was held in such high regard, she had such an enormous impact,” the former staffer said.

“I want her to be held to account,” she added. “I’m pissed.”

The second question: Was UATX a hard-right project from the start? Based on my reporting, I don’t think it was. I was struck by the sincerity of the commitment to free speech and open inquiry from so many of the people with whom I spoke. A few were Trump supporters, but many more were best identified as anti-woke moderates or liberals. The university’s saga has a strong sense of historical contingency — that it could have gone quite differently had some high-leverage moments gone otherwise. A notable example is the episode surrounding Dan’s alleged violation and expulsion, which several former staffers and faculty suggested was exploited by the Straussians as evidence of dysfunction in their successful second coup attempt.

A more helpful frame for making sense of this story is the one described by Michael Strambler in the article Avishai reposted prior to her firing: the near irresistible temptation humans feel to become convinced of the correctness of their positions. But certainty is incompatible with democracy and the academy, explains Ilana Redstone, a professor of sociology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Campaign; she is also a co-founder of the Mill Institute and was briefly associated with UATX.

Redstone says open inquiry requires three premises: Any claim can be questioned, questioning something doesn’t mean it’s wrong, and exploring an idea that someone thinks is odious doesn’t mean that someone wants to sign onto it. The paradox of democracy is that it can undo itself. One can exercise their free speech to advocate against free speech or use their vote to elect someone with authoritarian impulses. That’s the price of civil liberties. “If you really want to be the institution that is committed to open inquiry, to the pursuit of truth, et cetera,” says Redstone, “all of your own claims have to be subject to questioning.”

By its nature, a university — like democracy — invites the unbidden. It’s impossible to predict how students and faculty will exercise their freedom. The prospect that they would be allowed to speak and think freely, without fear of cancellation, is what made UATX’s original vision so exciting.

The ultimate irony is that UATX fell prey to the very impulses that its founders and supporters so detested. “It’s easy to see when other people lack these things,” Redstone said. “It’s harder to see in themselves.” Redstone hastens to add this isn’t just a failure at UATX. It’s fair to ask whether any university lives up to these ideas. Fair to ask, too, whether any institution can truly commit itself to first principles or if the instinct to shape outcomes and inject one’s personal politics is irresistible.

“Open inquiry demands that you accept imperfection and occasional embarrassment, and constitutionalism demands that you admit and correct mistakes publicly and open inquiry,” Marietta, the former UATX faculty member — and current professor at University of Texas-Knoxville — told me. But, he added, “Most people who want to control something want to control it.”

When students returned for UATX’s second year, it was difficult not to notice the drift. The Tuesday night speaker series, at which attendance is mandatory, leaned unmistakably rightward — guests included Patrick Deneen, originalist judge Amul Thapar and Catherine Pakaluk, a Catholic University business school professor who’d written Hannah’s Children, about the 5 percent of American women who have five or more children.

Finally on Oct. 1, UATX delivered the coup de grace and announced Kanelos’ resignation. We can’t be entirely certain of his side of the story, but one thing was abundantly clear.

The pluralists had lost.

.png)

English (US)

English (US)