“The depravity of man is at once the most empirically verifiable reality and the most intellectually resisted fact.”

The name of the man who made this pronouncement may not mean much to many readers now. Yet the world he warned about has arrived all the same, whether his name is remembered or not.

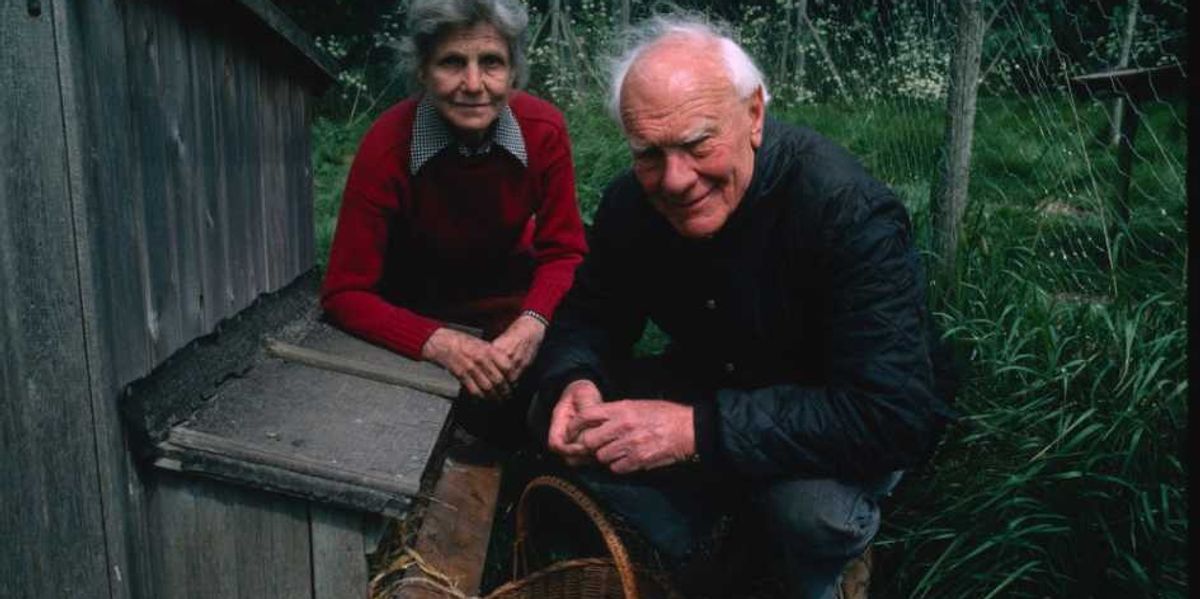

When Malcolm Muggeridge — a British journalist and broadcaster who became a public figure in his own right — died in 1990, many of his fears still felt abstract. The moral strain was visible, but the structure was holding. Progress was spoken of with confidence, and freedom still sounded uncomplicated.

'I never knew what joy was until I gave up pursuing happiness.'

Today, those assumptions lie in pieces. What he distrusted has hardened into dogma. What he questioned has become unquestionable. We are living amid the consequences of ideas he spent a lifetime probing.

Theory meets reality

Muggeridge was never dazzled by modern promises. He distrusted grand schemes that claimed to perfect humanity while refusing to reckon with human nature. That suspicion wasn’t a pose; it was learned. As a young man, he flirted with communism, drawn in by its certainty and its language of justice. Then he went to Moscow. There, theory met reality.

What he encountered was not liberation but deprivation. Hunger was rationalized as hope. Cruelty came wrapped in benevolent language. Compassion was loudly proclaimed and quietly absent. The experience cured him of fashionable idealism for life. It also taught him something harder to accept: Evil often enters history announcing itself as virtue, and the most dangerous lies are told with complete sincerity.

That lesson stayed with him. In an age once again thick with certainty, that insight feels uncomfortably current.

Pills and permissiveness

Yet Muggeridge’s critique extended beyond politics. At heart, he believed the modern crisis was spiritual. God had become an embarrassment, sin a diagnosis, and responsibility something to be displaced by grievance. Pleasure, once understood as a byproduct of order, was recast as life’s purpose. The result, he argued, wasn’t freedom but loss.

This realism shaped his opposition to the sexual revolution. Long before its consequences were obvious, he warned that freedom severed from restraint wouldn’t liberate people so much as hollow them out. He mocked the belief that pills and permissiveness would deliver happiness. What he anticipated instead was loneliness, instability, and a culture increasingly medicated against its own dissatisfaction.

Muggeridge also understood the media with unsettling clarity. As a journalist and broadcaster, he watched newsrooms trade substance for spectacle and truth for approval. When entertainment becomes the highest aim, he warned, reality soon becomes optional.

By the end of his career, Muggeridge had dismantled nearly every modern promise. Fame proved thin. Desire disappointed. Professional success brought no lasting peace. Skepticism could clear the ground, but it could not explain why nothing worked.

A skeptic stands down

When after more than a decade of exploring Christianity, Muggeridge finally entered the Catholic Church in 1982, the reaction among his peers was disbelief bordering on embarrassment. This was not the impulse of a sentimental seeker but of one of Britain’s most famous skeptics — a man who had mocked piety, distrusted enthusiasm, and made a career of puncturing illusions.

Friends assumed it was a late-life affectation, a theatrical flourish from an aging contrarian. Muggeridge himself knew better. He had not converted because Christianity felt safe or consoling, but because, after a lifetime of alternatives, it was the only account of reality that still made sense.

As he had written years before in "Jesus Rediscovered," “I never knew what joy was until I gave up pursuing happiness.”

That sentence captures the logic of his conversion. Muggeridge did not arrive at faith through nostalgia or temperament. Christianity did not flatter him. It named pride, lust, and cruelty plainly, then offered grace without euphemism. It explained the world he had already seen — and himself within it.

RELATED: Chuck Colson: Nixon loyalist who found hope in true obedience

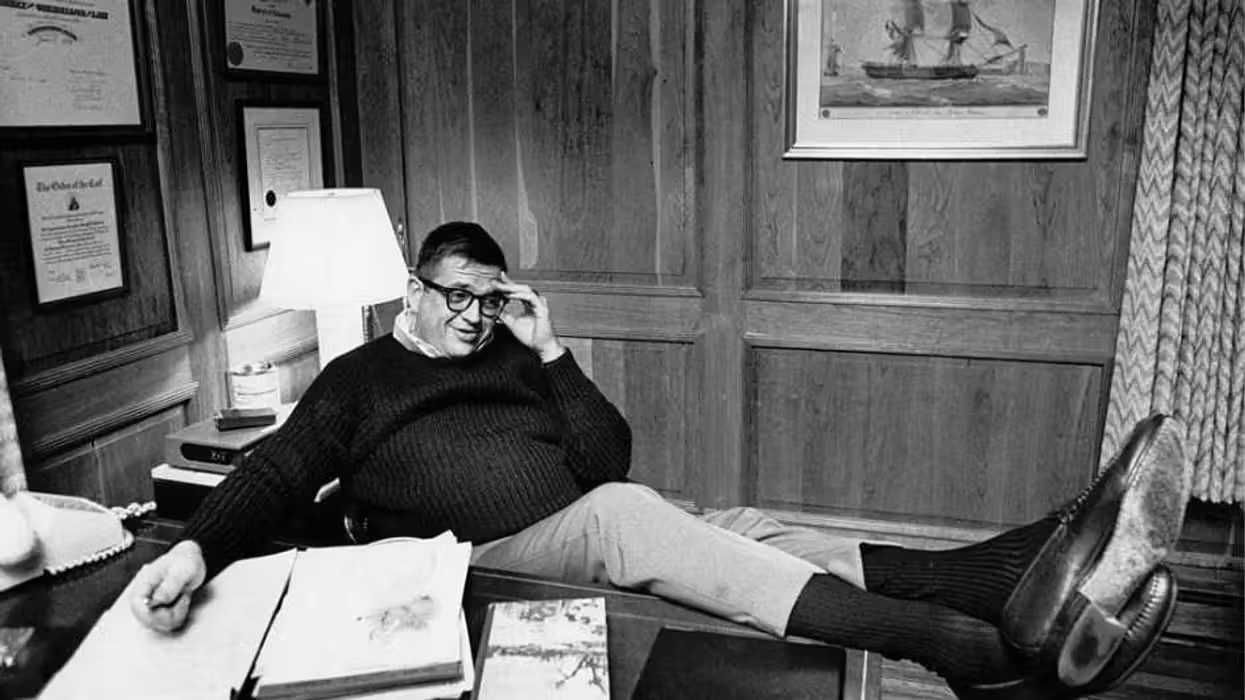

Washington Post/Getty Images

Washington Post/Getty Images

Truth endures

His Catholicism was not an escape from seriousness but its culmination. He believed human beings flourish within limits, not without them; that desire requires direction; that pleasure without purpose corrodes. Christianity endured, he argued, not because it was comforting but because it was true.

After his conversion, Muggeridge did not soften. He sharpened. The satire retained its bite. The warnings grew more direct. But they were no longer merely critical. Skepticism had given way to clarity — not because he had abandoned reason, but because he had finally stopped pretending it was enough.

More than three decades after his death, Muggeridge’s voice sounds less like commentary than like counsel. The world he warned about has arrived. What remains is the stubborn relevance of faith grounded in reality — and the freedom that comes only when truth is faced, rather than fled.

.png)

3 hours ago

4

3 hours ago

4

English (US)

English (US)