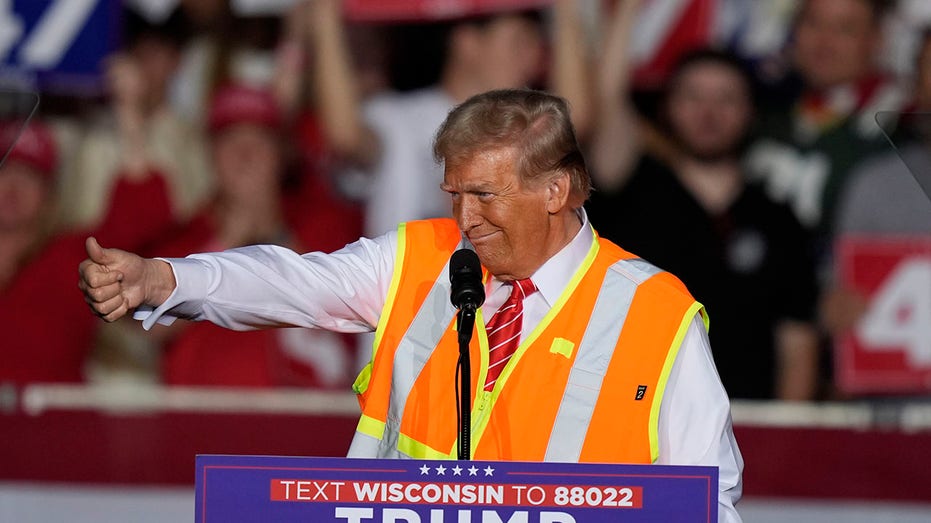

The texts and calls came not long after dawn, when it had been clear for hours that former President Donald Trump would reclaim the White House with an emphatic victory.

There were Democrats eager to make the case that President Biden could have run better, that, unlike Vice President Kamala Harris, there was no video of him arguing in favor of giving transgender surgery to prisoners. And why was she surrounding herself with celebrities rather than running as a tough-on-crime prosecutor, the most plausible way she could play against liberal orthodoxy?

At the same time there were the pro-Harris Democrats who were eager to argue that their research indicated that the sex-change-for-felons ad against Harris didn’t do nearly as much damage to her as those commercials linking her to the deeply unpopular incumbent. The same president who proved, they noted, with his comments in the final weeks of the campaign why he should have been shelved long before July. Oh, and get a load of this internal polling data showing how deep in a hole Harris was in every battleground state upon claiming the nomination.

The Biden sympathizers want to pin her loss on, well, her. And the Harris defenders believe Biden’s undeniably at fault for creating the forbidding political environment she proved unable to overcome.

The early-hours recriminations, though, only highlight the denialism of both factions in the wake of what will be the first GOP popular vote victory in two decades. This failure has many fathers.

First, it was the height of irresponsibility for Biden to insist on running for reelection in his 82nd year. It was also an abdication of leadership by his advisers and elected Democrats to never even question his determination to seek a second term until he forced their hand with a catastrophic debate performance. You know what ad would have replaced the trans surgery spot, had Biden not quit? An endless loop of his unintelligible answers at that debate.

It's also rich of the president’s loyalists to criticize someone who was only the nominee because then-candidate Biden made her his running mate in 2020. He revived Harris’s career after her flop of a primary bid, kept her on the ticket this year despite her low approval ratings and then crowned her within minutes of dropping out of the race in July. With the Democrats’ next-generation talent on deck, Harris would never have been a competitive candidate for her party’s nomination had Biden not made her vice president in the first place.

At the same time, how can Harris’s defenders grumble about being dragged down by Biden when she could not find one substantive policy issue on which to break from the unpopular incumbent? She waited three months, blurted out on “The View” that she couldn’t think of any difference with Biden and then eventually settled on vowing not to be “a continuation of” the current administration. Pressed again for differences, she’d drift into her housing proposal.

Yes, she was pressed into difficult circumstances, but where was the daring? There was no full-throated attempt at defensive politics and reassuring the country she’d govern from the center and reject extremists in both parties. And exit polls suggest that she paid a price for that with independent voters. If the other side assails you as a liberal without any clear and sustained response, well, voters will believe the attacks. Given the scale of difficulty she faced — and, yes, how bad that initial, internal polling was — why not take some risks?

Many people, inside and outside her campaign, tried to convey as much to her. One of them was her former adviser in California, Brian Brokaw, who in late October sent a last-ditch memo to her campaign urging her to confront “extremes across the political spectrum, far right or far left” and “name names” of the GOP lawmakers she’d work with on bipartisan legislation.

Brokaw wasn’t the only one pleading with Harris to more aggressively make clear how she’d lead and even challenge her own party.

Another longtime Harris adviser in California, Sean Clegg, sought to include language in her closing speech in Washington more directly contrasting Trump’s catering to the extremes and her commitment to govern from the middle.

Harris, though, avoided any unscripted encounters for weeks after jumping in the race. She performed well at her convention and sole debate, the two events for which she had ample preparation time. But she offered no big-picture rationale for running and no real answer for how she’d substantively break from the status quo. It was “turn the page” and platitudinous variations on Americans having more in common than not and Trump being a low character.

This is not to dismiss her challenge: there are, sadly, no small number of voters who were uneasy with her because she's a woman, Black or both.

Yet since her first years in elected office, Harris has been cautious to a fault. And here she was once again, at a moment that demanded risk. As with other steps of her career, Harris was best when working from a script and unsteady when forced to speak extemporaneously. Faced with deep structural challenges — the unpopularity of incumbents worldwide and a multi-racial, working-class realignment at home — she was badly outmatched. Talking about Trump’s “enemies list” and her “to-do list” was, in hindsight, laughably short of the moment.

She may have done the best she could. As one person close to her told me Wednesday, there was no example of her privately confronting Biden on immigration or the Middle East. Claiming any real break with him would’ve had to have effectively been invented.

And here again is where Biden must shoulder some of the blame. He picked somebody who had been senator for two years before running for the White House. Her only political grounding was in deep-blue California and a race-to-the-left presidential primary; she had never spent significant time campaigning for votes in Green Bay or Saginaw. And beyond criminal justice issues, she had no real policy expertise.

Upon entering the White House, she was given a thankless assignment (immigration) and otherwise nudged to handle Democratic constituencies. She clashed with the West Wing, some denizens of which had little faith in her, and quickly burned through staff before finally stabilizing her office.

Needless to say, Harris was never sent to a VFW convention or Farm Bureau gathering. Then, basically overnight, she had to introduce herself in the Midwest, a region she knew largely from what was in her briefing binder. Of course, her grasp of the Mideast also was largely derived from her briefing papers.

It was all a high-wire act.

Perhaps she could have emerged as a stronger candidate with more time, perhaps after a second term as vice president and in a better political environment. Or maybe her lack of any considered ideology or conviction —Ronald Reagan’s conservatism or Bill Clinton’s third way — would have doomed her whenever she ran.

The most compelling defense of her is that her loss was pronounced enough, the party’s retrenchment with non-white voters profound enough, that no Sister Souljah moment on, say, women’s sports would have appreciably helped her.

Democrats don’t just have a Harris or Biden problem. Their challenge is far deeper. They have a voter problem.

.png)

English (US)

English (US)