In Pennsylvania, the handwringing and recriminations started almost as soon as the essential 2024 battleground state was called for Donald Trump.

How did Philadelphia, the Democratic bulwark, deliver such an anemic margin for Kamala Harris? What explains the bellwether counties that Donald Trump wrested back after Joe Biden flipped them to the Democratic Party? And what happened in rural Pennsylvania, where the Harris campaign made an effort to show the flag and yet still lost 30 of the state’s 67 counties by more than 40 points?

It was a story that repeated itself across the electoral map, in swing states and non-competitive states alike. The Democratic coalition that delivered a convincing victory to Biden just a few years earlier simply disintegrated Tuesday, leaving the party stunned and disoriented over the scope of the destruction — and the GOP suddenly invigorated.

Not all the votes are counted yet, but the architecture of Trump’s victory is clear.

He managed to squeeze even more votes out of rural America — and that includes gains with rural Black voters. He continued to make significant advances with Latino voters, from the Southwest to the Acela Corridor. In big, diverse urban places — like Houston’s Harris County or Chicago’s Cook County — he pared down traditionally large Democratic margins. Many of the populous suburbs that so thoroughly rejected him in 2020 lost their anti-Trump edge. Even the biggest college counties appeared to lose the sense of urgency and outrage that marked their 2020 results.

And so, the Blue Wall crumbled, and the Sun Belt vanished for Democrats. Trump is currently on track to sweep the seven swing states and win a victory in the popular vote.

Here are the places that explain what happened.

Southeast Michigan

Vote-rich metro Detroit doomed Trump’s chances of winning Michigan in 2020. This year was a different story.

Four years ago, Detroit’s Wayne County and suburban Oakland County buried Trump, particularly as Oakland County turnout surged to 75 percent. This time around, Oakland’s turnout was down slightly and Harris pulled 112,000 fewer votes than Biden out of the state’s two most populous counties.

Oakland had been a top performer for Nikki Haley in the Republican primary — she won one-third of the vote against Trump — which made it a natural setting for one of the three Harris-Liz Cheney town halls. Yet that failed to make a big difference as Trump improved on his performance there over 2020.

Heavily Democratic Wayne County saw an even steeper drop-off, reflecting Muslim and Arab American anger toward the Biden administration’s continued support for Israel’s military offensive in Gaza and Lebanon. Trump, who once proposed banning immigration from Muslim countries, nevertheless cultivated the support of local Arab and Muslim leaders, culminating in a 9-point shift toward the GOP there. His performance was inflated by significantly increased support in Dearborn, Dearborn Heights and Hamtramck — all of which have heavy concentrations of residents of Middle Eastern descent.

Northern Virginia

Joe Biden made significant gains in 2020 over Hillary Clinton’s already winning performance in Northern Virginia. On Tuesday though, the region that’s home to over a third of the state’s population suddenly hit the brakes and shifted to the right. Harris’ performance dropped by 5 points in suburban and exurban Loudoun and Prince William counties. In Fairfax County, the state’s population giant across the Potomac River from D.C., Harris was down 4 points. The outcome was never in doubt in any of those places but the diminished margins helped make the state more competitive than in 2020. It’s one reason why Virginia could be called for Biden at 7:36 pm — roughly a half-hour after the polls closed — and why it wasn’t called for Harris until 11:42 pm this year.

South Texas

It was one of the biggest stories of the 2020 presidential election: Trump’s unexpected strength in the predominantly Latino Rio Grande Valley. Back then, he flipped just one county. This year, Trump painted the entire border red — from the RGV all the way north to Eagle Pass’ Maverick County. Among the counties Trump carried: Starr County, which is 97 percent Hispanic and hasn’t voted Republican for president in over a century. Just eight years ago, Trump lost Starr to Hillary Clinton by a 79-19 percent landslide.

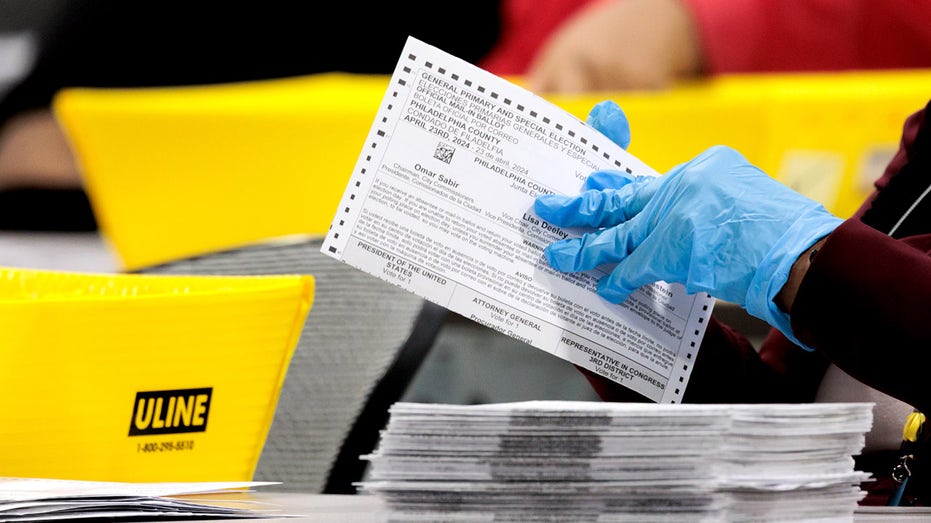

Philadelphia and its suburbs

In advance of Election Day, Philadelphia’s Democratic Party boss, former Rep. Bob Brady, laid out the yardsticks for success. If Harris wins a margin of over 500,000 votes in Philly, she’ll win, game over. But if she’s closer to 450,000, “it’s going to be tight, that’s not going to be an early night.”

While there are still some votes to be counted, Harris’ margin of victory wasn’t even close to that: just 412,000. Compare that to Biden’s 2020 margin: 471,000 votes. There are lots of reasons for the drop-off, but one of them stands out: In the 114 majority-Latino precincts in Philadelphia, Trump’s share of the vote grew from 6.1 percent in 2016 to 21.8 percent in 2024, according to a Philadelphia Inquirer analysis.

The Philly numbers were bad enough — a huge Democratic margin out of Pennsylvania’s biggest city is essential to success for any Democratic campaign. But they were compounded by the Democratic fall-off in the giant collar counties surrounding the city: Bucks, Chester, Delaware and Montgomery. After playing a key role in sinking Trump’s chances in 2020, all of them shifted in his direction by at least three points; Trump even managed to flip Bucks County, marking the first time it went red since 1988.

Central Florida

Trump’s thumping victory in Florida was embroidered with a number of notable developments. None were more eye-catching than the results in Orlando’s Orange County and neighboring Osceola County, which are home to large Puerto Rican communities. Despite the consternation surrounding the “island of garbage” controversy, the two fast-growing counties lurched to the right this year. Osceola went so far as to flip to Trump — a 15-point shift from 2020. The result capped a stunning Trump-era evolution: In 2016, Osceola gave Hillary Clinton a commanding 60-36 percent win. Eight years later, Trump carried the county.

Miami-Dade County

Florida saw a handful of its major metro areas flip to Trump on Election Night. Jacksonville’s Duval County and St. Petersburg’s Pinellas County, both of which voted narrowly for Trump in 2016 before flipping to Biden in 2020, flipped back to the GOP fold. Tampa’s Hillsborough County made an even harder right turn — it voted for Trump after delivering a comfortable 7-point win to Biden in 2020.

The bigger story was Trump’s break-through in Miami-Dade County. Under Florida’s old political model when it was a real battleground, Democrats needed to run up the score in Miami-Dade to offset their losses elsewhere. Biden failed to do that in 2020, and it cost him the state: The Trump administration’s close attention to Miami’s Cuban American community, and his campaign’s anti-socialist and law and order messaging paid off, not just among Cuban Americans but with Venezuelan Americans and other Latino groups.

Still, Biden managed to win Miami-Dade, even if it was by a diminished margin. This year? Harris wasn’t even close. Trump won by 11 points, representing the biggest shift of any of the state’s 67 counties.

Southern Minnesota

The southern Minnesota House district Tim Walz once represented in Congress was brimming with so-called Pivot Counties, a collection of roughly 200 counties across the nation that voted twice for Barack Obama before flipping to Trump in 2016. They tend to be whiter, less affluent, less educated and smaller in population than the U.S. average and more rural or small-town oriented.

Biden, who outperformed Hillary Clinton in much of rural and small-town America, was able to win back three of southern Minnesota’s Pivot Counties — Blue Earth, Nicollet and Winona counties. A Democratic presidential ticket featuring Walz, who represented these areas first as their congressman and then as governor, might have seemed optimal in the battle to keep these counties in the party fold. But even Walz’s presence on the ballot failed to prove convincing to these voters, who decided to turn back to Trump; the former president dominated in Greater Minnesota — that is, the areas outside the Democratic Twin Cities region.

McKinley County, New Mexico

The Trump campaign’s low-key efforts to court Native American voters appeared to have paid dividends. Across the map, in traditionally Democratic, predominantly Native American counties, Trump made noticeable inroads. The two Montana counties that saw the sharpest shifts to the right were Glacier and Blaine counties, both of which have Native American majorities. Robeson County in North Carolina, home to the Lumbee tribe, saw a 9-point shift to the right — the biggest red shift of any county in the state.

New Mexico’s McKinley County saw an even bigger movement toward Trump. Harris still won comfortably, but the county, which is 81 percent Native American and home to members of several different tribes, shifted 14 points to the right.

All of this came despite the Harris campaign’s assiduous courting of the Native American vote. In late October, Walz campaigned in Window Rock, Arizona (the capital of the Navajo Nation government) — accompanied by Deb Haaland, the Interior secretary who is Native American — where he praised Native American military veterans and discussed rural health care. President Joe Biden also traveled in October to the outskirts of Phoenix, to the Gila River Indian Reservation, and formally apologized for the federal government’s role in running boarding schools where thousands of Native American children faced mistreatment and forced assimilation.

Despite the Democratic focus on Arizona, which has the highest percentage of Native Americans of the seven battleground states, Trump appears to be making sharp gains. With 60 percent of the vote counted in Apache County (which is 72 percent Native American), he is running far ahead of his 2020 pace.

Northeastern Pennsylvania

One big question in Pennsylvania was how Harris would fare in the Republican-trending land of Biden’s birth. Heavily Catholic and white working class, demographically older, Scranton’s Lackawanna County and neighboring Luzerne County posed a significant challenge for Harris. Luzerne had already broken hard for Trump in 2016 and stuck with him four years later; Biden’s 2020 margin in Lackawanna didn’t inspire confidence that it would remain in the Democratic fold, especially without him atop the ticket.

In the end, Harris managed to narrowly hold on to Lackawanna but with the same slightly diminished margins that doomed her elsewhere in the state. Luzerne, meanwhile, continued its rightward march, delivering its highest percentage yet to Trump — 60 percent.

Bristol County, Massachusetts

In presidential races, Massachusetts and Rhode Island provide some of the most reliably blue turf in the nation. But Bristol County, right on the border between the two states, is virtually dead even at the moment — Harris leads Trump by less than a percentage point. Four years ago, Biden easily won there, 55-42.

What’s unusual here is that it’s been decades since any of Massachusetts’ 14 counties have voted for a Republican presidential candidate. Key to Trump’s enhanced performance in the cluster of towns and cities that make up Bristol County are New Bedford and Fall River. New Bedford, where Trump’s support spiked this year, offers a glimpse into Trump’s non-traditional coalition — the city is roughly a quarter Latino, with a relatively sizable Puerto Rican population and a higher-than-average percentage of foreign born persons. In addition, Trump flipped the city of Fall River, which like New Bedford has a relatively low percentage of residents with college degrees and a relatively high percentage of foreign-born people.

Johnson County, Iowa

Outsized margins by big, liberal college counties were an essential element in Biden’s 2020 victory. But the same degree of anger and outrage toward Trump doesn’t appear to be reflected in the 2024 results. Harris still won all these places, typically by very big margins. But the margins are often smaller than in 2020, or off a percentage point or two in county after county.

There are any number of possible reasons — among them, the Gaza issue or Trump’s traction with young male voters — but they won’t be known until all the results are complete and the voting data is more closely scrutinized.

In Iowa City’s Johnson County (home to the University of Iowa), there’s a 5-point shift toward Republicans. In Iowa State’s Story County, it’s 7 points. The shifts were slightly smaller in Michigan State’s Ingham County and the University of Michigan’s Washtenaw County. It was a similar story in the University of Georgia’s Clarke County, Penn State’s Centre County and the University of Florida’s Alachua County. Travis County, home to the University of Texas and the state capital, delivered a Democratic margin this year that was close to 50,000 votes smaller than in 2020.

As for the University of Wisconsin’s politically super-charged Dane County, naturally it produced more Democratic votes. But it was modest by its standards — just 7,200 votes more than in 2020.

Eastern North Carolina

The nation’s eyes were fixed on Charlotte’s Mecklenburg County and Raleigh’s Wake County and the size of the Harris margins they’d produce — and they ended up underperforming relative to 2020. But the rural counties of eastern North Carolina also played a role in preserving Trump’s hold on North Carolina. Trump made notable gains with Black voters across the region, flipping Nash County and nearly flipping Wilson County. He also ran several points ahead of his 2020 pace in majority Black Hertford and Northampton counties. It wasn’t enough to overcome Harris in those counties, but it was a signal of the Democratic ticket’s weakness with both rural white and Black voters.

It was a pattern that repeated itself in southern Virginia and in South Georgia.

Milwaukee and its suburbs

Trump underperformed in Wisconsin’s so-called WOW counties (Waukesha, Ozaukee and Washington), the traditional Republican fortress surrounding Milwaukee, in both 2016 and 2020. With Waukesha and Ozaukee seemingly drifting leftward, the trio figured to be no match as a counterbalance to Madison’s Dane County and Milwaukee County this year. Yet Trump cauterized the wound in the Republican suburbs and accomplished something more important — small and steady gains nearly everywhere else in the state. It was a prosaic victory, not nearly as sweeping or as eye-catching as in other states. But with Dane and Milwaukee counties performing at about the same clip as in 2020, it was just enough to win a state that was decided by an incredibly small amount of votes. With over 95 percent of votes in, Trump was ahead by less than 30,000 votes.

Lehigh Valley

Easton’s Northampton County has an uncanny habit of siding with the presidential winner and this year was no different. It was one of three counties in the state to flip from Obama to Trump in 2016, and then it bounced back to Biden in 2020. This year, it flipped back to Trump along with another noted Pennsylvania bellwether, Erie County.

Neighboring Lehigh County also moved in Trump’s direction, though not enough to give Trump the win. What’s notable in both places is that Trump advances came in two counties with sizable Latino populations. His increasing traction with Latino voters in Allentown, Bethlehem and Reading (which is just outside the Lehigh Valley in nearby Berks County) was obvious during the campaign, but it was assumed the caustic remarks made at his late-campaign rally at Madison Square Garden would prove costly given the considerable Puerto Rican communities in the region.

Highway billboards appeared in Allentown, Reading and Philadelphia featuring a photo of a beach in Puerto Rico with the message: “This isn’t garbage and neither are we. Boricuas, this time, we vote for her.” But the election results suggest the controversy didn’t move the dial very much at all.

.png)

English (US)

English (US)