MOSCOW, Idaho — On a Sunday morning earlier this spring, Pastor Doug Wilson stood behind the pulpit at Christ Church to deliver his weekly sermon. His message for the congregation was clear and uncompromising. The gospels, he said, teach that life offers a choice between two irreconcilable alternatives: “Christ,” he said, raising his right hand, “or chaos.”

The audience — about a thousand congregants in modest button-downs and understated sundresses — listened intently from the pews, interrupted only by the occasional babble of one of the many babies in their midst. Sunlight filtered into the sanctuary from three gothic windows behind the altar, casting shadows on the austere walls and pitched ceiling. Outside, the green hills of northern Idaho unfurled like a plush rug all the way to the horizon.

From the pulpit, Wilson, a burly 71-year-old with a white lumberjack beard and a commanding baritone, turned his attention to the world beyond the sanctuary. Given the choice between Christ and chaos, he said, the world has chosen chaos. “We live in a relativistic time, and that relativistic time has taken as its motto, ‘Reality is optional,’” Wilson intoned. “That’s why you have people saying that a girl can be a boy, and a boy can be a girl.”

For the past 50 years, Wilson has been trying to convince America that it has made the wrong choice —that it should choose “Christ,” as he put it, instead of chaos. But Wilson isn’t a conventional evangelist. He is, by his own description, an outspoken proponent of Christian theocracy — the idea that American society, including its government, should be governed by a conservative interpretation of Biblical law. Wilson’s body of work — made up of over 40 books, thousands of blog posts and hundreds of hours of sermons and podcast appearances — amounts to a comprehensive blueprint for a spiritual and political “reformation” that would transform America into a kind of Christian republic.

Since the 1970s, Wilson has built a sprawling evangelical empire around his theological principles. The capital of that empire is Moscow — pronounced “Mos-coe,” not like the capital of Russia — a small town in northern Idaho, where Wilson oversees a network of allied institutions that includes Christ Church, a publishing house, a classic Christian grade school, a Christian liberal arts college and a ministerial training program. Beyond Moscow, the network of churches that Wilson founded in the late 1990s — called the Communion of Reformed Evangelical Churches, or CREC — has grown to include over 150 congregations across four continents; an association of classical Christian schools that Wilson co-founded in 1993 now counts over 500 member schools across the country.

The scope of his empire notwithstanding, Wilson has spent much of his career outside the conservative mainstream, which has distanced itself from his frank defense of theocracy, his ultra-patriarchal views on gender relations and his reactionary stances on race and “the war between the states,” as he still calls the Civil War. (On the “About” page of his blog, Wilson describes his politics as “slightly to the right” of the Confederate general Jeb Stuart.) Online, Wilson has cultivated a punk-rock aesthetic designed to foster his reputation as the “based” intellectual bad boy of American evangelicalism: In a promotional video posted at the height of the conservative backlash to “woke” media companies in 2023, Wilson used a skull-and-crossbones-emblazoned flamethrower to torch oversized cardboard cutouts of various Disney princesses and social media companies, all while puffing on a fat cigar.

But in recent years, Wilson has been making inroads into the Republican establishment, aided by a growing audience for his work among allies of President Donald Trump and the MAGA movement. Last year alone, Wilson appeared as a guest on Tucker Carlson’s podcast, spoke at an event organized by the MAGA operative Charlie Kirk, delivered a speech on Capitol Hill at an event hosted by the MAGA-aligned talent pipeline American Moment and was given a prominent timeslot at the National Conservatism Conference, the premier annual get-together for the nationalist-populist right in Washington. In January, Wilson received his most significant political boost to date when Pete Hegseth —who is a member of a CREC church in Tennessee and publicly praised Wilson’s work — was confirmed as Trump’s secretary of Defense.

When I sat down with Wilson in Moscow earlier this spring, he told me that he doesn’t know Hegseth personally, but he cheered his selection to the highest civilian post in the U.S. military. ((In May, after my visit to Moscow, Wilson briefly met Hegseth during a visit to his church in Tennessee, as first reported by Talking Points Memo.) “It’s gratifying to have like-minded people — people around the country who think the way I do and who worship the way I do — coming into places where they can do something about it," Wilson told me.

Wilson and his allies are moving quickly to cement their burgeoning influence in Washington. Later this summer, Christ Church will open its first outpost in the capital, led by Wilson and a rotating group of pastors from the CREC. The new church has earned the support of powerful players in the MAGA movement: Its inaugural prayer services, planned for mid-July, will be held at an event space operated by the Conservative Partnership Institute, the Trump-aligned think tank run by former Republican Sen. Jim DeMint and ex-Trump chief-of-staff Mark Meadows. In a blog post titled “Mission to Babylon,” Wilson explained that Christ Church is seeking to make inroads with “numerous evangelicals who will be present both in and around the Trump administration.”

Wilson has good reason to believe those conservative evangelical elites are receptive to his message. In recent years, a growing number of Republican elites clustered around the “New Right” of the GOP have been looking to Wilson’s work as a kind of how-to manual for injecting a hardline conservative form of Protestant Christianity into public life — a project that ranges from outlawing abortion at the federal level to amending the Constitution to acknowledging the truth of the Bible.

Chief among the sources of Wilson’s appeal on the right is his defense of a masculinist and explicitly patriarchal style of evangelicalism: Women are barred from holding leadership roles at Christ Church, and women in CREC communities are expected to submit to their husbands. Wilson, who has written several books on marriage, masculinity and childrearing, is a gleeful critic of feminism, which he has lampooned in blog posts with titles like “The Lost Virtues of Sexism.” At times, he’s ditched the high-minded theological rhetoric and referred to various women as “small-breasted biddies,” “lumberjack dykes” and “cunts.”

His taste for provocation is evident across his blog, “Blog & Mablog,” where his posts — ranging from weedy interventions in theological debates to Biblical defenses of spanking — are written in a wry and jocular style. (Yes, profanity is permitted, if used in a godly way.) In person, though, Wilson comes across more like a grandpa than the flamethrowing pirate of his online persona. When I met him for our interview in Moscow, he was wearing a sweater vest and slip-on sneakers, and he visibly shrunk from my suggestion that he had become a serious public intellectual on the right. “I am comfortable calling myself a ‘public intellectual for the deplorables,’” he said with a sly grin. “I hope that my writing on cultural engagement gets read by people who are in a position to do something with it.”

His primary message for those people, he told me, is that “theocracy” isn’t a scary concept.

“When you say ‘theocracy,’ people think Gilead and women in red dresses, or the Ayatollah’s Iran,” he said. But, he argued, that’s only because most people are thinking of “ecclesiocracy,” or political rule by clerics and church officials. What he has in mind for America is closer to a return to the political order embodied by “the Constitution of the late 18th century and early 19th century,” with a weak central state, a small-R republican form of government and a high tolerance for displays of Christian faith in the public sphere.

This distinction, however, is unlikely to assuage Wilson’s critics, who have cast him as the vanguard of the rising forces of “Christian nationalism” in America. Wilson and his allies have winkingly embraced the term as a badge of dishonor: In 2022, his allied publishing house, Canon Press, published a book called “The Case for Christian Nationalism” by the Protestant political theorist Stephen Wolfe. But whatever its merits as a marketing tool, the term undersells the scope of Wilson’s political vision: His ideal political arrangement, he told me, would be a kind of international confederation of Christian nations that he calls “mere Christendom,” harkening back to the alliance of Christian nation-states that dominated Europe during the Middle Ages.

As his audience in Washington has grown, though, Wilson has been sketching out some more concrete plans for shifting America in his preferred direction. When we spoke in Moscow, he cheered the Trump administration’s effort to “dismantle the administrative state,” and he suggested the Supreme Court should build on its recent decision to overturn Roe v. Wade by re-evaluating Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 case recognizing a constitutional right to same-sex marriage.

Beyond these near-term goals, Wilson has floated some more fundamental changes to America’s political system: Amending the Constitution to include reference to the Apostles’ Creed, restricting office holding to practicing Christians and changing voting practices to award votes by household, with the default vote-holder being the male head of the household. His long-term goal, he said, is to inspire a grassroots Christian reformation that would excise the whole idea of secularism from American law and society.

He admits that this reformation would represent a “huge” departure from America’s current political order, and that even some of his more modest reforms could only be brought about via constitutional amendment — or, if that fails, civil strife.

“I’m fond of saying that reformations never happen to the polite background sound of golf applause,” Wilson said. “It would be tumultuous.”

Would it be violent, I wondered?

“Well,” he said, chuckling, “that depends on the bad guys.”

The town of Moscow sits on the eastern edge of the Palouse, a swath of surreally green grassland that cuts across southeastern Washington, northeastern Oregon and a small patch of western Idaho. Despite the steadily expanding population of “kirkers” — as members of Christ Church call themselves, borrowing the Scottish word for church — the town is still home to a sizable population of liberals, thanks in large part to the presence of the University of Idaho’s flagship campus.

The combination of ultra-conservative Christians and left-leaning university types living in close proximity has turned Moscow into an on-the-nose symbol of life in a divided America: On the five-block stretch of shops that makes up Moscow’s downtown, a slew of kirker-owned businesses stand side-by-side with organic food co-ops and coffee shops displaying Pride flags and Black Lives Matter signs in their windows. On the Sunday morning of my visit, the kirker who offered to drive me to church gently ribbed me after I asked him to pick me up at one of the liberal-aligned coffee shops downtown. I had no choice, I protested. All the kirker-owned ones were closed for the sabbath.

The origins of Moscow’s divide date back in large part to Wilson’s arrival in 1975. Wilson was born in Annapolis, Maryland, where his father attended the U.S. Naval Academy before becoming an evangelist and the manager of a Christian bookstore. In 1971, after Wilson had left home, his parents moved to Moscow, believing that the town’s proximity to two major universities — Washington State University is just over the border in Pullman, Washington — made it an ideal location for evangelizing.

When Wilson arrived in Moscow after his own stint in the Navy, he told me one afternoon as we drove around town in his pickup truck, his plan was to stick around for a year or two before heading east — probably to Laramie, Wyoming — to open a bookstore of his own. But life, as it does, intervened: He fell in love with a Christian girl in town, got married, had a daughter and started preaching to a small congregation.

At the time, Wilson was a Baptist who had fallen under the sway of the Jesus Movement — the revival of charismatic evangelicalism that swept through the countercultural and Hippie movements in the 1970s — but he remained a theological conservative. “I wasn’t a druggy or hippie that got converted,” Wilson assured me. “I was a Navy guy.” He also leaned to the right politically, thanks in large part to a teenage fascination with William F. Buckley and National Review. In 1980, he and his wife, Nancy, bought their first television set to watch Ronald Reagan beat Jimmy Carter on election night.

Yet as Wilson began pastoring, he grew troubled by what he saw as the “schizophrenic” state of American evangelicalism. Throughout the 1970s, evangelicals had swung to the right in response to the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision, but Wilson thought their political activism was conspicuously devoid of any meaningful grounding in Protestant theology. In response, he started reading books by a group of conservative Reformed theologians — writers like Francis Shaeffer, who posited that all knowledge was grounded in the truth of Biblical revelation, and R.J. Rushdoony, who argued that all Biblical law, including the Old Testament law, still applied to the contemporary world. Most of the thinkers Wilson was drawn to were “postmillennialists,” meaning they believed the second coming of Christ would occur after an extended period of Christian dominion on earth. As Wilson came to realize, this position implied a fundamentally activist approach to politics: Christians could hasten Christ’s return by building a godly society in the here and now.

From these various sources, Wilson formulated a political theology that he came to call “theocratic libertarianism.” It was grounded in his broader theological vision — an ultraconservative form of Reformed Presbyterianism that traces its roots back to the 16th century French reformer John Calvin — which Wilson summarized with a simple mantra: “All of Christ for all of life.”

In Moscow, Wilson explained that his political philosophy is not theocratic in the commonly understood sense of a government run exclusively by the church. To the contrary, he maintains that God ordains earthly authority in three separate spheres of life: the church, the family and the civil government. Within each of these spheres, the relevant authorities must abide by scriptural commandments. In the familial sphere, for instance, parents must educate their children according to Biblical principles, and wives must subordinate themselves to their husbands in accordance with a covenantal view of the family. In the sphere of civil government, officials should strive to bring the law in line with Biblical commandments, although those principles don’t have to be applied “woodenly,” as Wilson put it: Governments do not have to enforce the Biblical mandate that households build balustrades on their roofs, but they should enforce the principle that homeowners are liable for risks incurred on their property.

Above all, Wilson believes, the three spheres of earthly authority must remain separate. Governments should not infringe on families’ responsibility to educate their children — the basis of Wilson’s critique of public education — and the church shouldn’t own and operate businesses, which is why individual kirkers, rather than the Church, operate all the coffee shops and boutiques in downtown Moscow.

Taken together, Wilson’s theology provided a sturdy basis for his conservative politics: It was pro-capitalist, patriarchal, skeptical of big government and scornful of progressive visions of a society without hierarchy or holy men. Having arrived at that theory, Wilson moved to put it into practice in Moscow. In 1981, when his eldest daughter was reaching school age, he and two other kirkers opened an independent Christian academy, called the Logos School, to avoid having to send their children to the local public schools. Thirteen years later, when the first graduating class from Logos was preparing to head off to college, Wilson helped open an independent liberal arts college, New Saint Andrews, to continue their education in Moscow. To keep up with the ballooning volume of printed material coming out of the church and the schools, Wilson also founded his own publishing house, Canon Press, in 1988. (He has since sold it to his son and a business partner.) Following Wilson’s entrepreneurial example, a growing number of kirkers bought property around Moscow and opened their own businesses.

Soon enough, Wilson’s corner of Moscow began to resemble a microcosm of the Christian city-states that he had read about in his studies, with Christ Church at its center. “This is all one fabric,” Wilson told me.

When the coronavirus pandemic arrived in 2020, Wilson was not initially opposed to closing Christ Church: After all, his philosophy of “sphere sovereignty” allowed the state to take reasonable steps to protect public health, including temporarily shutting businesses and churches. But after a few weeks of holding services online in accordance with local policies, Wilson grew itchy. He came to believe that the government was using the shutdowns to test how much control normal citizens would tolerate. “And it became our responsibility to demonstrate: not very much,” he told me.

So on a cloudy day in September 2020, Wilson organized a gathering in downtown Moscow to protest the lockdowns. About a hundred kirkers showed up in the parking lot outside Moscow’s city hall, where they stood around a large wooden cross and sang psalms together. Partway through the demonstration, Moscow police officers arrived and arrested three kirkers on various charges. (All the charges have since been dropped, and the city reached a court-ordered settlement with the kirkers in a civil lawsuit stemming from their arrests.)

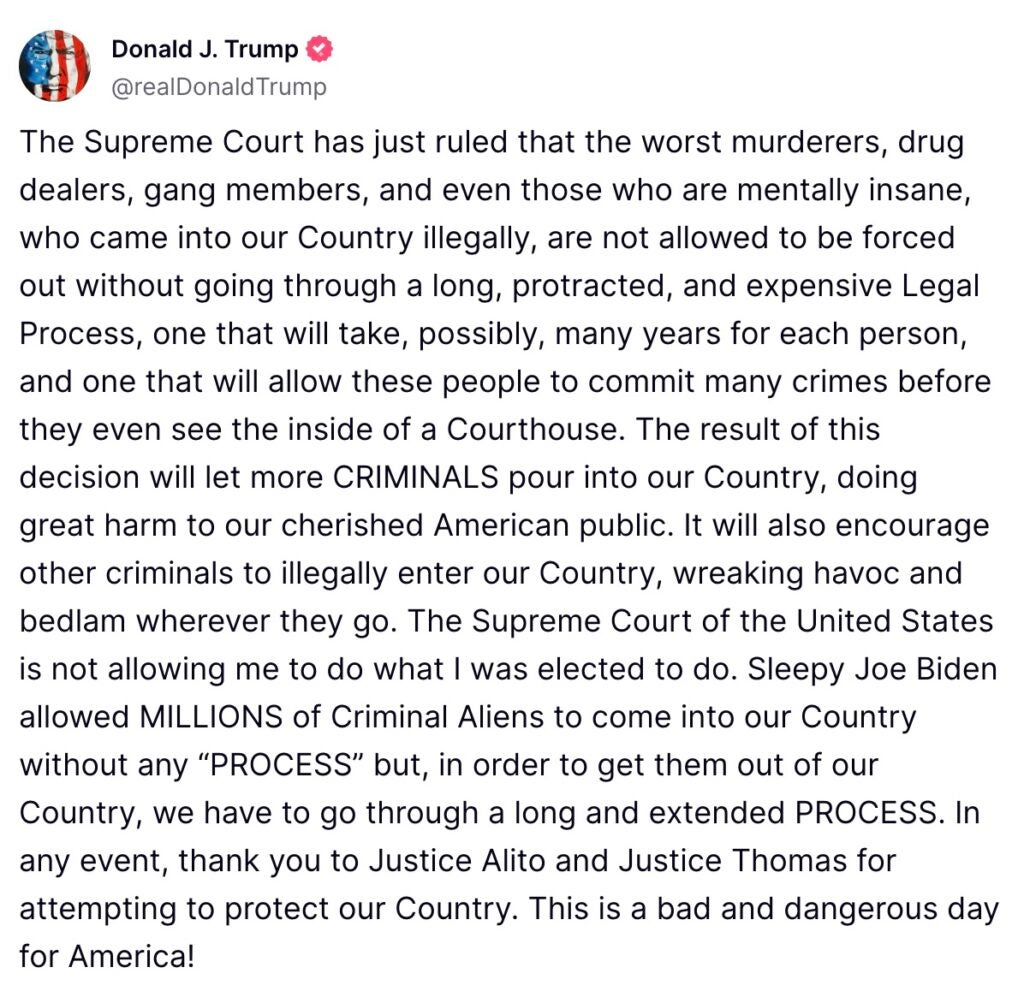

The following day, footage of the arrest went viral on Twitter, and then got picked up by conservative cable news. Within two weeks, the video appeared on Donald Trump’s Twitter feed. “DEMS WANT TO SHUT YOUR CHURCHES DOWN, PERMANENTLY,” the president wrote in a post retweeting footage of the arrests. “HOPE YOU SEE WHAT IS HAPPENING. VOTE NOW!”

It was a rare moment of mainstream exposure for Wilson and his followers. Even as evangelicals entered the Republican coalition through the 1970s and 1980s with groups like the Moral Majority and Focus on the Family, Wilson’s heterodox theology and his hard-right politics had kept him on the fringes of the conservative movement. He occasionally dabbled in national politics — in 1992, he served as the Idaho state coordinator for Howard Phillip’s far-right U.S. Taxpayer Alliance, according to documents from the time — but he otherwise stuck to local politics. He didn’t find much success there, either: In the early 1980s, he mounted a campaign for a seat on Moscow’s city council and lost badly. “I was very successful at getting the liberal vote out,” he joked.

Wilson’s political exile was reenforced by his habit of staking out politically poisonous positions in various historical controversies, particularly revisionist debates about the Civil War. In 1996, for instance, Wilson co-authored a pamphlet with the Calvinist theologian J. Steven Wilkins that offered a qualified Biblical defense of slavery, arguing that antebellum slavery “produced a genuine affection between the races that we believe we can say has never existed in any nation before the War or since.” In 2004, the pamphlet — which Canon had pulled from the market because of citation errors — became a flashpoint in series of protests against Wilson’s growing influence that briefly consumed Moscow.

Despite the fallout from the slavery controversy, Wilson caught his first real glimpse of mainstream success in 2007, the year that the British journalist and New Atheist provocateur Christopher Hitchens published his anti-religion jeremiad God Is Not Great. In conjunction with the publication of the book, Hitchens put out a public call for practicing theists to debate him, and Wilson answered his challenge. The two men went on to publish a written back-and-forth in Christianity Today, which Hitchens enjoyed so much that he invited Wilson to hit the road with him for a series of live public debates throughout early 2008. The debates — as well as the surprisingly buddy-buddy relationship that developed between the two men — were captured for a feature-length documentary that debuted in 2009.

The film received middling reviews, but it earned Wilson a degree of legitimacy he had previously lacked. “Wilson is becoming someone who even those minding their own business in the noncontroversial ‘mainstream’ cannot afford to ignore,” a journalist for Christianity Today wrote at the time.

But it was the viral lockdown protest that finally catapulted Wilson onto the national stage. Within months of the incident, “a massive refugee column” of conservative evangelicals fleeing states with more restrictive lockdown measures started to arrive in Moscow, Wilson told me. To accommodate the influx of new arrivals, he helped open two more churches in the greater Moscow area, bringing the total population of kirkers to over 3,000 people — double the community’s size from 2019.

But people weren’t just moving to Moscow to escape pandemic restrictions; they were also eager to hear what Wilson had to say.

“There are things that we would be talking about 25 years ago that would just get us dismissed as nutters,” Wilson said. “But after the pandemic, what we were saying seemed a lot more intelligible and, for many people, compelling.”

In October 2021, Nick Solheim, the co-founder of the conservative talent pipeline American Moment, traveled from Washington to Moscow to record an episode of the organization’s podcast with Wilson. During the pandemic, Solheim had read several of Wilson’s books and was impressed by his willingness to bring a conservative theological perspective to contemporary political questions. “He had a wiser approach than many about how Christians should think about political issues,” Solheim told me. After the podcast episode published, Solheim was struck by the amount of buzz it generated in young conservative circles in Washington. “A lot of Hill staffers were very interested in it,” he recalled. “They would make these offhand comments like, ‘If you ever brought him to D.C and did an event, I would definitely be there.’”

So that’s what Solheim did. In September 2023, Wilson appeared in the hearing room of the Dirksen Senate Office Building for an event hosted by American Moment, dedicated to making “the Christian case for immigration restriction.” At a table at the front of the room, Wilson sat alongside Rep. Chip Roy, the Freedom Caucus Republican from Texas, and Russell Vought, the former (and now current) director of the Office of Management and Budget under Trump.

The American Moment event helped puncture whatever remained of the informal embargo that had kept Wilson outside of respectable conservative circles. Soon enough, Wilson was popping up in more and more prominent spots: In April 2024, he was a guest on Tucker Carlson’s podcast to discuss his views on Christian nationalism, earning Carlson’s praise as “one of the rare American Christians pastors who is willing to engage on questions of culture and politics.” In July 2024, he spoke at Turning Point USA’s “Believers Summit,” hosted by the MAGA activist Charlie Kirk. That same month, he appeared at the National Conservatism Conference in Washington, organized by the conservative writer and activist Yoram Hazony. (Solheim’s co-founder at American Moment, Saurabh Sharma, was as a co-organizer of the event.)

The flurry of activity also marked the culmination of Wilson’s own embrace of the MAGA movement. In 2016, Wilson had been skeptical enough of Trump that he declined to vote for him. “This New York tycoon comes out of nowhere, he was a Democrat before, and he says, ‘Oh yeah, I’m pro-life’? I just didn’t believe that,” Wilson recalled. By the end of Trump’s first term, he had been won over by the administration’s record on abortion and other religious issues. By 2024, he was ready to leap into the fray.

It was last year at “NatCon,” as the event is called, that Wilson’s entrance into the conservative mainstream was most evident. Between speeches by Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley and JD Vance, Wilson sat down with Hazony and Albert Mohler, the president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. The symbolism of this arrangement was not lost on Wilson’s followers. For decades, Mohler had been a leading face of the conservative evangelical establishment that had distanced itself from Wilson. Now, the two men were appearing onstage together, affirming their shared goal, as Mohler put it, of “maximizing the Christian commitment of the state and of the civilization.”

Trump’s reelection delivered a more immediate victory for Wilson in the form of Pete Hegseth’s selection as secretary of Defense. In 2022, Hegseth — along with his wife and seven children — moved from New Jersey to a suburb of Nashville, Tennessee, where the family joined a CREC congregation, and his children began to attend a classical Christian school affiliated with Wilson’s American Association of Classical and Christian Schools. On at least one occasion, Hegseth has praised Wilson’s writings, which he said he encountered through a church reading group, and has claimed that New Saint Andrews, which Wilson helped found, is one of the few colleges that he would pay for his children to attend. Just this past week, Hegseth hosted the CREC pastor Brooks Potteiger — who is close with Wilson and recently appeared with him at his church in Tennessee — for a prayer service in the Pentagon’s auditorium. (In a statement, chief Pentagon spokesperson Sean Parnell confirmed that Hegseth is a “proud member” of a CREC congregation and “very much appreciates many of Mr. Wilson’s writings and teachings.”)

When I asked Wilson about Hegseth’s nomination, he said he was aware Hegseth was a member of a CREC church before his selection, though he maintains he doesn’t have a personal relationship with him aside from their brief encounter in Tennessee. “I don’t have a pipeline to the Defense secretary,” he said.

Wilson did admit to me, however, that he took one step that “could be regarded as a rear-guard action” to protect Hegseth’s nomination. In November, Wilson helped organize and write a statement called the “Antioch Declaration,” which denounced the “rising tide of reactionary thinking” — including “neo-pagan doctrines of the Nazi cult” — within evangelical circles. This statement was widely interpreted as Wilson’s effort to distance himself from a younger cohort of Reformed pastors and adjacent right-wing influencers who have flirted with — or, in some cases, outright embraced — various racist, antisemitic and ethnonationalist ideas.

Yet Wilson told me that the statement was designed, at least in part, to preempt any attempts by Democrats to force Hegseth to answer for these ideas. “One of my pastoral philosophies is [to think] ‘What would I do if I were the devil?’ and then I try to do the opposite,” Wilson told me. “Well, if I were the devil, I would try to get some CREC person to stand up in public somewhere and say, ‘I hate the Jews,’ and then get footage of it and show it at the confirmation hearing.”

Wilson’s diabolic expectations didn’t materialize — Hegseth’s church membership didn’t come up during his Senate confirmation hearing, despite several media reports tying him to the CREC — but that was all the better for Wilson. “That was simply an anticipatory defensive move,” he told me.

On Saturday night in Moscow, Wilson invited to me his family’s weekly sabbath dinner, hosted at his daughter’s house in the hills of the Palouse. When I arrived at the house with Wilson, there were about a dozen adults milling around a large living room nursing glasses of wine and beer, as streams of children — too many to count — bobbed and weaved between them. After some polite schmoozing, we took our places at long tables set up in the living room: the men at one end, the women at the other and the kids on their own. After leading the group in a prayer and a song, Wilson sat quietly at his place, looking reserved. As dinner wrapped up, I picked up my dish to clear it — until I realized I was the only man with a dish in hand.

After dinner, I joined the men around a fire pit on the back patio to smoke cigars and drink whiskey. Once again, Wilson sat quietly, declining a cigar as the men chatted about their families and their favorite cuts of meat. During my interactions with Wilson, I had gotten the sense that his outlaw image is mostly the product of clever marketing cooked up by the young and very online men he has deputized to run the various parts of his empire. His deputies largely copped to this dynamic. “I have a feeling that cigar he smokes in the [promotional] videos is maybe the one cigar he smokes a year,” said Brian Kohl, the CEO of Canon Press and a native of Moscow.

Marketing aside, Wilson has been embroiled in some very real off-camera controversies. In recent years, several former members of Christ Church have accused Wilson of mishandling or downplaying cases of sexual assault, marital violence and child abuse within the CREC community. (“They sure have,” Wilson wrote in a statement when I later asked him about those accusations. “Look at them go.” He has denied wrongdoing as part of the “library” of responses to various controversies that he maintains on his blog.) Other former members argue that, regardless of Wilson’s personal involvement in specific incidents, the church’s teachings about the patriarchal nature of sexual relations either excuse or implicitly encourage these sorts of acts, especially marital violence against women. (“Blerg,” Wilson wrote when asked to comment on this potential connection. On his blog, he denies that he condones sexual abuse.)

In particular, Wilson’s critics argue that some of his past writings about sex — including his statements that “the sexual act cannot be made into an egalitarian pleasuring party,” and his description of heterosexual sex as “A man penetrates, conquers, colonizes, plants. A woman receives, surrenders, accepts” — amount to a tacit defense of marital violence. “These pastors told me a wife is not allowed to tell her husband no,” a former kirker who said she was the victim of marital abuse told Vice in 2021.

Despite these criticisms — or perhaps because of them — Wilson’s deputies have made Wilson’s bad-boy aesthetic the centerpiece of their marketing across the greater Christ Church universe. In a recent smash-cut video advertisement for New Saint Andrews College, a roguish-sounding narrator appeals to young men who are “willing to hoist the Jolly Roger and Johnny Cash’s favorite finger,” as a picture of the country star flipping the bird flashed in the background. The reality I found on the ground was a bit less rock-n-roll: As I walked around New Saint Andrews’ main building one afternoon, I saw a lot of plain-looking teenagers reading thick copies of Augustine’s City of God and practicing their Latin declensions on blackboards.

Yet something about the college’s marketing seems to be striking a chord with young evangelicals. NSA’s student population has grown rapidly in recently years, from just under 150 undergraduates in 2020 to over 300 in 2024, and it has bought more real estate in downtown Moscow, much to the chagrin of its liberal neighbors. When I spoke with the college’s president, an Oxford-educated academic named Ben Merkle, he attributed the recent growth of the college’s population to an ongoing shift in the attitudes of young conservative Christians. After the dislocations wrought by the pandemic, Merkle said, young Christians aren’t just looking to their churches to provide a spiritual vision. They also want a comprehensive vision of a Christian life, grounded in a real intellectual tradition and robust cultural institutions — which is why the Catholic Church, with its centuries of doctrines and ornate ceremonies, has attracted so many young conservative converts. Christ Church and its affiliated institutions are betting that Reformed evangelicalism can offer something similar. “Men in their twenties are leaving evangelicalism for Roman Catholicism or Eastern Orthodoxy because they look over there and say, ‘This is a coherent life,’” Merkle told me. “What they lost is that the Protestants were the premier purveyors of exactly that tradition.”

At the same time, the proliferating cohort of NSA graduates has expanded Wilson’s universe of influence and brought him into direct contact with various ascendent power centers on the right. Of particular note is a cluster of NSA graduates who have entered the world of “anti-woke” venture capital, which is serving as a beachhead of sorts for conservatives looking to make inroads in Silicon Valley. One of the most prominent players in this area is New Founding, a venture capital and real estate firm founded by the Harvard Law School graduate Nate Fischer and backed in part by the tech right stalwart Marc Andreessen, and which employs two NSA graduates.

The firm isn’t sectarian in its mission — its leadership includes a handful of Baptists and Catholics — but it’s not cagey about the theological underpinnings of the project: On its website, it describes its mission as “to shape institutions with Christian norms and orient them toward a Christian vision of life, of society, and of the good.” Among the projects that New Founding has backed are an internet publication called American Reformer, which has published Wilson and provides a regular forum for debates within the Reformed evangelical world, as well as an initiative called the Highland Rim Project, which is trying to build a Moscow-like Christian community in Appalachia.

“There is this idea that Christianity is going to win in the long-term, so we’ve got to go out and build for the long haul,” said Joshua Clemans, a graduate of NSA who now works as a partner at New Founding. Along with another New Founding employee and NSA graduate named Santiago Pliego, Clemans is part of an extended social universe — dubbed the “Theo Bros” by some researchers and journalists who have covered it — that connects Moscow to various reactionary power centers in Silicon Valley and Trump’s Washington. Fischer, who is now the CEO of New Founding, is a former fellow at the Trump-aligned think tank the Claremont Institute, and New Founding podcast, hosted by Clemans and Pliego, features a who’s who of guests from the “dissident right” and Silicon Valley reactionary circles. When JD Vance was selected as Trump’s running mate in July, Clemans posted a picture of himself and the New Founding team smiling alongside Vance, with the caption “Our guy.”

Clemans was circumspect about Wilson’s role in this world. “He’s more like the grandpa familias,” he said. “A lot of people read and respect his blog, so his opinion carries a lot of weight.” But the reality is that Wilson’s ideas have become so commonplace in this ecosystem that many people who don’t read his blog still adhere to them, Clemans said. “It’s not just Doug. It’s a very robust and decentralized network of people who are interested in pushing those ideas.”

Every couple of weeks, Wilson hosts a podcast for Canon Press called Doug Wilson and Friends, where he sits down with figures from the greater Christ Church universe for unstructured chats about the issues of the day. Culture war skirmishes are never far afield from these gab sessions, but in the months since the presidential election in November, the conversations have drifted more and more into discussion of Trump’s Washington.

The results can be somewhat jarring to an outside ear. Wilson and his allies are fluent in the language of conservative evangelicalism, able to back up their defenses of Trump with a litany of Bible verses and references to obscure theological texts. But they are also well-versed in the patois of the bookish and very online right. In a recent episode titled “Trump World has Overtaken Clown World” — borrowing a term coined on the alt-right internet to describe the upside-down state of globalized liberal society — one of Wilson’s associate pastors expressed his hope that Trump would “raze to the ground the edifice of bureaucratic managerialism.” When I first heard this, I had to remind myself that I was listening to an evangelical talk show and not a podcast from the Claremont Institute or some other tweedy MAGA think tank.

Wilson has, predictably, been following the early developments of the Trump administration with a mix of glee and joyous disbelief. “It’s like Christmas every morning,” he told me. He was especially enthusiastic about the administration’s effort to slash the administrative state, led by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency.

It was, I thought, an odd choice for a Christian conservative like Wilson, considering DOGE was so closely associated with Musk, a twice-divorced technologist with a slew of children born out of wedlock and no discernible attachment to the Christian faith. When I asked him how he thinks about his own role in a political coalition that includes plenty of openly non-Christian conservatives, Wilson drew a distinction between “allies” — people who are fighting for the same cause that he is — and “co-belligerents,” or people who share his same enemies but not his aims.

The important thing for conservative evangelicals, he said, is to find political leaders who can steer the entire coalition in the right direction. When I asked him who in Washington he saw as viable leaders in this mold, he mentioned some libertarian stalwarts, like Sens. Rand Paul and Ted Cruz, as well as some MAGA populists like Hawley, Vought and Vance. He said that he thinks the vice president is “shrewd” and “very smart,” but he was disappointed that he had watered down his anti-abortion position during the campaign to curry favor with Trump. I wondered if he would be comfortable voting for a Catholic like Vance.

“The question is compared to what?” he said. “Compared to whatever Menshevik is going to be nominated by the Democrats?”

This uneasy alliance with figures like Musk and Vance speaks to a broad political challenge facing conservative evangelicals like Wilson. Despite consistently high levels of evangelical support for Trump, Wilson is entering the conservative mainstream at a moment when the Republican Party is trying to project a more secular self-identity, in large part in response to the influx of non-religious conservatives who have followed Trump into the party. Although Trump has followed through on some of the religious right’s key priorities, like overturning Roe, he has also diluted religious conservatives’ influence by attracting an array of secular constituencies — from Barstool conservatives to transhumanist tech-bros — to the GOP.

All this means that Wilson faces steep odds of persuading the Republican Party to put his more explicitly theocratic ideas into practice anytime soon. Yet Wilson sounded largely unconcerned when I asked him about this dynamic. He told me that he’s focused on the political long game rather than influencing policy in the near term, and that his theory of political change is premised on the idea that politics is downstream of culture, which in turn is downstream of worship — meaning that the best way for Christians to shape politics is to change what people hear from the pulpit on Sunday.

Yet for all the fault lines dividing MAGA, Wilson believes the conservative movement is trending in the right direction, at least philosophically. As he wrote in a recent blog post, Trump’s coalition includes an eclectic mix of “Catholic integralists,” “NatCon conservatives,” “Christian classical liberals who hate the label of Christian nationalism” and “guys wearing bowties who work for think tanks in DC” — none of whom actually agree with each other about the type of world conservatives should aspire to create. But the thing that increasingly holds this group together, Wilson wrote, is the argument he’s been making for years: “the grand secular experiment of civil governance has been a moral and political disaster of the first order.”

“If modern secularism were a school of culinary arts, we are all of us now staring at a heaping plate of warmed-over dumpster scrapings,” he wrote. “We all agree on that.”

As we wrapped up our conversation in Moscow, Wilson told me that he doesn’t think he’s moved into the conservative mainstream so much as the conservative mainstream has moved to include him. Twenty years ago, he said, “if you challenged [the liberal consensus] like I would have, you would have been laughed out of town.”

“But everything has disintegrated in the last few years,” he told me, “so when I say that the secular experiment has failed, a lot of Christians — and even non-Christians — say, ‘Yeah, it has.’”

On his visits to Washington, he added, he has been surprised to discover how many people are open to the basic idea that the secular liberal order in America is coming to an end, and that something else — maybe even a Christian theocracy — will eventually take its place.

“It’s very strange,” he said. “You agree? What?”

.png)

English (US)

English (US)