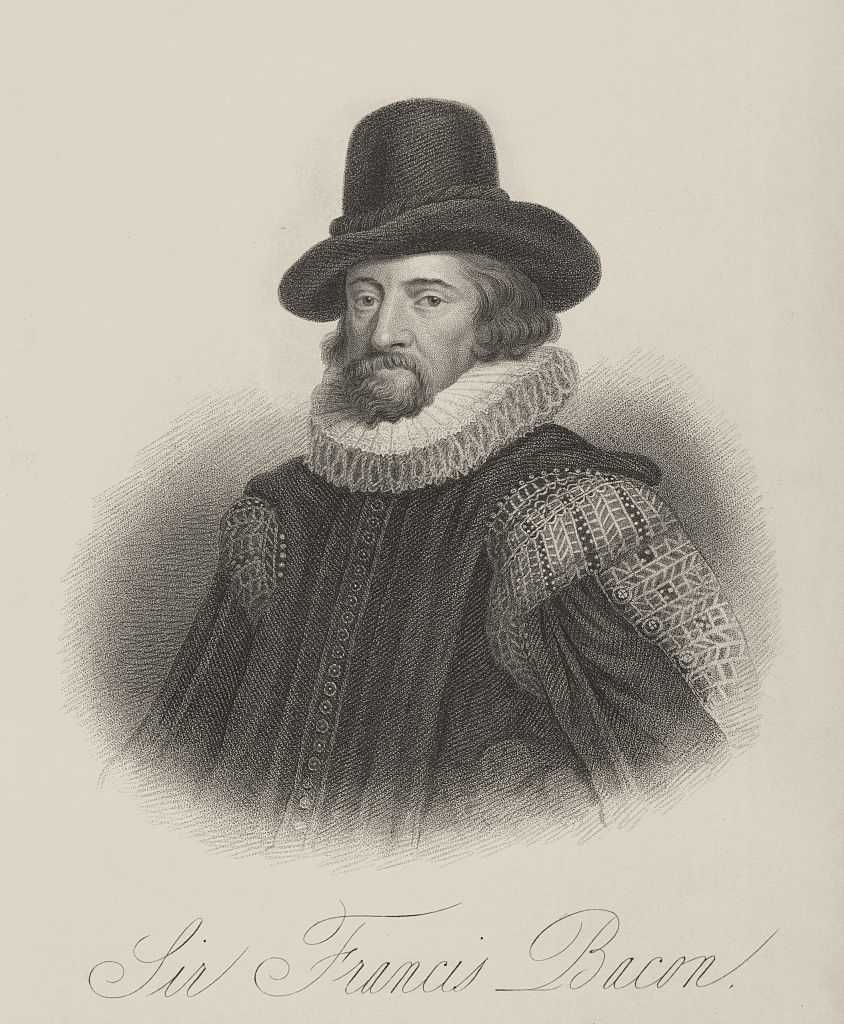

The story that modernity tells itself is one of technological progress. We have told this story for so long, with such unwavering conviction, that we have forgotten it has an author. When the Nobel committee awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in economics to Joel Mokyr, they were not merely recognizing a historian. They were footnoting the author of our prevailing narrative, a 17th-century English statesman who never invented a single device, but who successfully marketed ideas so potent that they would remake the world in their image. The story of our prosperity, Mokyr insists, begins with Francis Bacon.

It begins, more precisely, with a frontispiece. The engraving on Bacon’s 1620 "Novum Organum" depicts a ship sailing past the Pillars of Hercules, venturing out from the known world into an uncharted ocean. The motto beneath, “Many will travel and knowledge will be increased,” was not only a prediction but an exhortation. Before Bacon, knowledge was largely a matter of contemplation and study of classical authorities. He saw these as dead ends. Knowledge, he declared, ought to bear fruit in production. Its purpose was not merely to understand the world but to gain “dominion over creation” for the “relief of man’s estate.” Ipsa scientia potestas est. Knowledge itself is power.

This created the feedback loop that defines modernity: Scientific theory leads to new technology, and new technical problems spur further scientific inquiry.

This was the core of what Mokyr calls the “Baconian program”: a philosophical revolution that reframed humanity’s relationship with nature. Nature was no longer a given order to be accepted, but a set of secrets to be extracted, a force to be subdued. Bacon spoke of putting nature “on the rack” to force her to confess her laws. The goal was utility. The method was to marry the rational and the empirical, to unite the philosopher in his study with the craftsman in his workshop. In "The New Atlantis," he imagined a research institute called “Salomon’s House,” dedicated to inventing things. He was, in Mokyr’s description, a “cultural entrepreneur,” and the product he was selling was a particular vision of the future.

This product sold remarkably well. From the mid-17th through the 18th century, the Baconian program became the organizing principle of the European intellectual elite. The Royal Society of London, founded in 1660, adopted Bacon as its patron. Its members were not to take anyone’s word for the truth; they were to experiment and measure instead. Across the continent, a network of thinkers in the “Republic of Letters” spread the gospel of useful knowledge through correspondence and journals. The monumental French "Encyclopédie" was a direct descendant, an audacious attempt to catalog and disseminate all practical human knowledge, from mining techniques to political theory. The very idea that sharing knowledge leads to progress became an article of faith. This was the “Industrial Enlightenment,” a culture that not only hoped for improvement but actively engineered it.

RELATED: God made man in His image — will 'faith tech' flip the script?

Photo by NurPhoto/Getty Images

Photo by NurPhoto/Getty Images

The Industrial Revolution, in Mokyr’s telling, was not an accident of capital or coal. It was an intellectual achievement, the consequence of this cultural rewiring. James Watt did not improve the steam engine in a vacuum. He was a product of a new culture, a skilled mechanic familiar with the latest scientific theories on heat and pressure. His separate condenser was not a feat of solitary genius, but a manifestation of Bacon’s call to unite “know-why” with “know-how.” This created the feedback loop that defines modernity: Scientific theory leads to new technology, and new technical problems spur further scientific inquiry. The economic growth that followed was not just an increase; it was a phase change. It became sustained and exponential because of the cultural engine continuously driving it.

America inherited this engine and supercharged it. Benjamin Franklin was the archetypal home-grown Baconian, an inventor and scientist celebrated for his practical ingenuity. The nation’s founding ethos was steeped in the promise of both geographical and scientific frontiers. The 20th century saw the program institutionalized on a massive scale. Vannevar Bush, persuading the government to fund basic research after World War II, called science “the endless frontier,” an echo of Bacon’s ship sailing into the unknown. The Manhattan Project, the moon landing, the invention of the microchip — these were all expensive, elaborate vindications of a 400-year-old premise. The smartphone in your pocket is a Salomon’s House in miniature, a device built on centuries of accumulated knowledge, from quantum mechanics to materials science, all marshaled for the purpose of utility.

And yet one is left to wonder about the price of this story. The Baconian program gave us the power to relieve our estate, but it did so by teaching us to view nature as a resource to be exploited, a standing reserve for our own declared needs. The instrumentalism that gave us vaccines and the internet also gave us a world where we have become alienated from the very ground on which we stand. Bacon’s faith in progress was infectious, but it sidelined other ways of being, other stories that valued contentment over control, harmony over dominion. Mokyr’s great contribution is to show us that the modern economy is not a force of nature, but the result of a choice made long ago. He reminds us that the contemporary world we inhabit was first imagined. We live inside a 17th-century dream.

.png)

2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1

English (US)

English (US)