"What is a Christmas movie?”

This is probably a question you’ve heard before in passing. Most of us instinctively have a good idea of what one is, but more than likely, that understanding is rather inexplicable, abstract, or trapped in the minutiae.

Only by leaning into my Christian faith did I begin to see these films and the unique glow that turns a regular film into a Christmas film.

We all know the tropes of Christmas movies — Santa Claus, joy to the world, peace and goodwill toward men, white snow on a warm Christmas morning, jingle bells, presents under the tree, hot chocolate and eggnog, sugar plums, figgy pudding, Nativity scenes, et cetera.

For most people, Christmas is a feeling and an idea as much as it is a day on the calendar. However, trying to put the abstract into words is challenging. In my capacity as a film reviewer, amateur filmmaker, and member of the Music City Film Critics Association, I have spent more than three years talking with friends and puzzling over the question for fun. For the most part, this debate was a lively intellectual exercise between my philosopher and cinephile friends and me; I can recall one particularly fun session of debate with my girlfriend as we discussed the Aristotelian implications of the definition of Christmas movies.

As it will become clear in this text, though, the answer to the question, “What is a Christmas movie?” is surprisingly hard to narrow down and answer definitively.

This was a problem I set out to try to formally solve in late 2024, during a rare moment of adult life when I had the time to sit down for three months and binge-watch out-of-season Christmas movies, while attending to a lengthy family hospice situation. As strange as it felt spending the month of October bingeing on Christmas movies, it was enlightening. Surveying films between the years 1935 and 2024, one sees a number of patterns and tropes fly by, evolving with the culture year by year.

Subsequently I partnered with my good friends at the evangelical ministry Geeks Under Grace to put my ideas to paper, publishing 10 weekly articles on the subject between November and December 2024. But even as I was penning those first essays, I struggled to find the right words; I didn’t have an answer in mind from the outset, merely a series of arguments and anecdotes. I would need to find my thesis in the act of writing this book.

There aren’t enough books written about Christmas films as a genre. If there are many, they are buried under an ocean of histories for specific films, best-of collections, or works written by obscure academics.

It’s easy enough to find resources on the production history of "It’s a Wonderful Life" but less so about the subgenre that flows out of it. Much has been said about the great entries in the subgenre: how "Miracle on 34th Street" became the first financially successful Christmas movie in 1947; how "It’s a Wonderful Life" and "A Christmas Story" were popularized via television broadcasts; how "Mister Magoo’s Christmas Carol" became the first animated Christmas special specifically released for television in 1962; how 2003’s "Elf" is the last Christmas film to be considered a blockbuster.

There is less said about what connects these data points.

One of the few experts on the subject I found was Scottish scholar Tom Christie, who has published multiple books on the history of Christmas films in the past decade through Extremis Publishing, including "The Golden Age of Christmas Movies: Festive Cinema of the 1940s and '50s" and "A Totally Bodacious Nineties Christmas: Festive Cinema of the 1990s." The rest of the insight I found was buried in individual articles and YouTube essays, to which I owe a tremendous debt for helping me shape the greater picture. They helped me break through my writer’s block and made the connections I needed to complete the project.

However, the seeds of insight I found in my reading turned me away from the films themselves.

From first principles, there can be no understanding of Christmas movies without first understanding Christmas. And there is no understanding of Christmas without understanding religion, society, secularism, consumerism, and the nature of what American society considers “normal.” It was only through this that the seed blossomed into what I think is the best achievable conception of a Christmas film, and only by leaning into my Christian faith did I begin to see these films and the unique glow that turns a regular film into a Christmas film.

I apologize to any secular readers who may have picked up this book imagining it would be relatively areligious, but I must beg their pardon in the necessity to discuss these issues through the lens of theology. I’m a practicing Christian, and I cannot help but think of life through the lens of a high-church Protestant. However, Christmas is a Christian holiday (at least tacitly), and I don’t think it’s possible to completely excise Jesus from the day bearing his name — at least not without turning the holiday into a parody of itself.

Christianity teaches us that Jesus Christ, the second person of the Trinity, became flesh and walked among us. He was both fully God and fully man and became the hinge of history. He was a paradox, described in His Nativity by the apologist C.S. Lewis, “Once in our world, a stable had something in it that was bigger than our whole world.”

The idea that a God so seemingly wrathful, distant, and lawful would be so humble as to allow Himself to be born as a fleshy human baby to a peasant woman in the backwater of the Roman Empire is strange. But this is the event Christmas celebrates — a contradiction and a miracle; the fullness of history fulfilled in humility; the logos breaching into the world; a quiet resistance manifesting against the evils of this rebelling silent planet.

Reflecting on this and the modern reality of Christmas, an idea began to unfold slowly in my mind. The realization came to me that Christmas movies are not defined so easily but are defined by a connection to the supernatural. They are downstream of something greater, containing within them a small drop of the divine-like spring water filtering into a mighty river.

That water may no longer be clear and crisp, or even drinkable, but its flowing is evidence of a source.

Christmas movies are utterly unique in modern film due to the way we interact with them. They are a subgenre unto themselves, intertextually linked with other Christmas movies and the holiday itself, but it is that very intangible glow that makes them unique. They contain an essence of what Lewis once described, in his book "The Problem of Pain," as “the numinous”:

Those who have not met this term may be introduced to it by the following device. Suppose you were told there was a tiger in the next room: you would know that you were in danger and would probably feel fear. But if you were told, “There is a ghost in the next room,” and believed it, you would feel, indeed, what is often called fear, but of a different kind. It is not based on the knowledge of danger, for no one is primarily afraid of what a ghost may do to him, but of the mere fact that it is a ghost. It is “uncanny” rather than dangerous, and the special kind of fear it excites may be called dread. With the uncanny one has reached the fringes of the numinous.This is not to call Christmas movies dreadful but that they contain within them a sense of the supernatural, what we might call “awe.” Connecting with that awe is downstream of the supernatural source that created it. Christmas movies grab that stream like a third rail and feel electrified by it.

It may seem like a bit of a leap to say that mean-spirited and cynical movies like "Christmas Vacation" or "Bad Santa" are in some way a reflection of God’s divinity, but as we will come to see, the thing that sets Christmas films apart from other films is an embrace of the supernatural essence of Christmas.

A Christmas movie always contains an element of hope that warps cynicism and pain of its story toward an ideal.

A Christmas movie glows with Christmas spirit.

A phrase like “the true meaning of Christmas” does this too, alluding to some unspoken notion that culture agrees upon, that Christmas is meaningful because it changes people. It scratches upon something divine while remaining achingly human and unspecific.

That thing is not entirely limited to the faithful, as secular people enjoy Christmas too. Muslims, Jews, Buddhists, and atheists all celebrate Christmas in equal measure. And while I wouldn’t say they celebrate in the same manner as I do at the communion rail on Christmas morning, they are communing with something beyond the superficial layers of cheap plastic junk that Christmas would be if it were merely another day in December.

This book is the result of many months of thought and reflection, brought into the world by the good graces of my friends and colleagues who helped me write it, host it, critique it, and bring the original articles to fruition, here expanded to a thematically rounded 12 chapters. Each chapter has been revised to reflect the conclusions I discovered in the very act of writing the book. One often finds his destination only by setting out on an unknown journey!

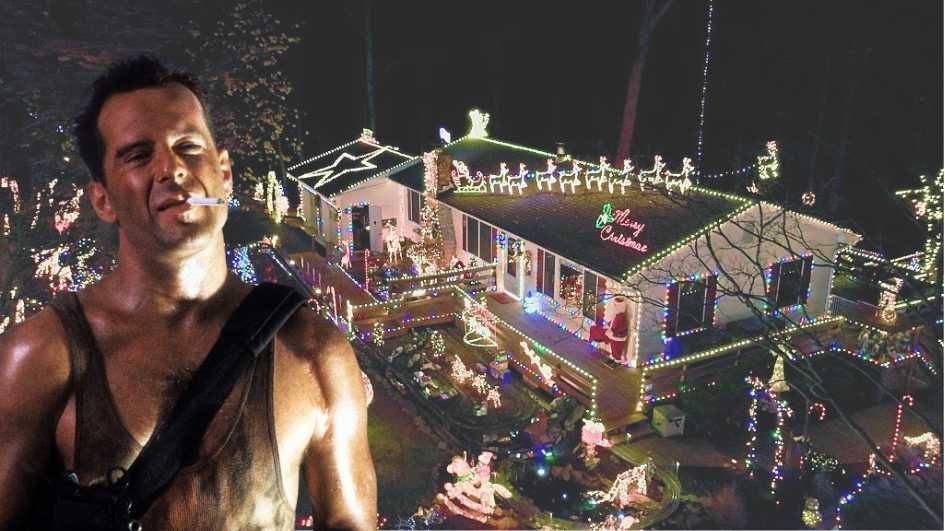

So let us start by asking the most immediate and controversial question and then let our understanding unfold: Is "Die Hard" a Christmas movie?

From there, we will discuss Christmas as a secular phenomenon; explore Christmas movies as a subgenre; the role religion, consumerism, normality, and nostalgia play in Christmas cinema; and close on the incarnational implications of Christmas films.

What is a Christmas movie?

Let’s find out!

The above essay was adapted from the book "Is 'Die Hard' a Christmas movie? And Other Questions About the True Meaning of Christmas Films," which is available here.

.png)

3 hours ago

1

3 hours ago

1

English (US)

English (US)