Within minutes of the announcement that the American conservative activist Charlie Kirk had died from an assassin’s bullet, statements of grief came pouring in from leaders across Europe. “An atrocious murder, a deep wound for democracy and for those who believe in freedom,” Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni wrote on X. “France expresses its deep emotion following the assassination of Charlie Kirk,” the French Foreign Ministry proclaimed. Despite the 31-year-old political provocateur once calling his country “a totalitarian third world hellhole,” British Prime Minister Keir Starmer said it was “heartbreaking that a young family has been robbed of a father and a husband.”

Other reactions were less subdued. “Charlie Kirk’s death is the result of the international hate campaign waged by the progressive-liberal left,” seethed Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, despite the fact that the murderer remained at large at the time and no motive was known. Jordan Bardella, leader of France’s far right National Rally, condemned the “dehumanizing rhetoric of the left and its intolerance.” The clearest example of European political divisions over the assassination is the fight that erupted in the European parliament over a request from the body’s far right bloc for a moment of silence in Kirk’s honor. After the motion was denied on procedural grounds, the Swedish Democrat MEP who backed it drew attention to the unfairness of it all by pointing to another martyred American, George Floyd, whose death at the hands of a law enforcement officer five years ago the parliament commemorated with a resolution condemning police brutality.

The murder in broad daylight of Charlie Kirk — someone who devoted his life to recruiting young people to join the right through the open exchange of ideas, and who leaves behind a wife and two young children — will have a dramatic impact on American politics and society the full extent of which is yet to be foreseen. Beyond the many practical changes that his assassination is likely to produce (fewer outdoor political events, increased calls for social media censorship, high-profile activists and pundits hiring private security details), his death prompts several extremely important questions. Will political leaders and influential media figures tone down the dehumanizing and apocalyptic rhetoric that has convinced so many Americans that violence is the only solution to their problems? Will our professors think long and hard about why over a third of American college students believe that employing violence to stop a campus speech is justified? Will everyday citizens diversify their media diets, or dig deeper into their rabidly partisan rabbit holes?

It’s the visceral reactions to this week’s tragedy in Europe, however, that I find most interesting. The easy answer for this phenomenon is that Kirk’s murder was an assault on the free society. Assassinating a public figure while he’s engaging in peaceful political activity is a blatant attack on the foundational values of the transatlantic community wherever one sits on the political spectrum. Other elements intensify the significance of the event. Kirk’s youth and ardency made him, in conservative eyes at least, something of a latter day Joan d’Arc, the televised spectacle of his slaying evoked the harrowing assassination of John F. Kennedy, and the setting of the university campus — where the pursuit of knowledge is supposed to be sacrosanct — made the attack that much more appalling. The social media fueled internationalization of politics also plays an important role; if one wishes to follow the political minutiae of Slovakia’s Gelnica province, never before has it been easier to do so. A Guardian story about Kirk’s influence published the day after he died featured bylines from Tokyo, Paris, Seoul, Taipei and Delhi.

Such factors cannot sufficiently explain, however, why vigils for Kirk popped up in London, Berlin, Madrid and Rome. Kirk was not an elected official, nor was he a traditional Republican.

He began his political life as a MAGA-red diaper baby, which makes the public statements by European leaders all the more remarkable. The insurgent Kirk, President Donald Trump’s most effective ambassador to the youth of America, represented something much larger than a domestic American political movement.

While future historians will determine the impact of Kirk’s death on American politics and society, his murder has made one thing abundantly clear: the unprecedented level of ideological convergence between the American and European right.

The reaction to Kirk’s death on both sides of the Atlantic attest to the synergy between Trump’s Make America Great Again movement and Europe’s ascendant populist nationalists. These forces are united in their strident opposition to mass immigration, skepticism of international institutions, aversion to anything that smacks of “globalism,” their unabashed patriotism, and loathing for the elites and expert class whom they portray, not without some justification, as having made a mess of things over the past 35 years. They feel under siege in a rapidly changing world and wish to set things back to a time before their countries were so multicultural, urban-dominated and internationally connected. These parties have formed strong networks and there is a great deal of ideological and rhetorical cross-pollination. Look, for instance, at the adoption of MEGA (“Make Europe Great Again”) as an acronymic credo, or the British chapter of Kirk’s tremendously successful youth organization, Turning Point UK, appropriating an international expression of solidarity coined 10 years ago after another shocking act of political violence: “Je Suis Charlie.”

In 2019, Trump strategist Steve Bannon launched an initiative to strengthen far-right parties across the continent, but his effort never took full flower. Since then, however, a series of populist right-wing electoral victories in the UK, France, Germany, Italy and (most significantly) the United States made what was once talked about seriously only in Orbán’s Budapest — a proto-Nationalist International — a reality. There’s few things Trump loves more than winning, and he has enthusiastically boosted the inchoate formation of a populist alternative to the traditional, bipartisan transatlantic alliance of yore. Trump is the furthest thing from a party man and has little time for the ornate rules and stuffy traditions that political parties exist to enforce. Like no president before him, he transcends his nominal party affiliation and has remade the GOP in his own image.

Not surprisingly, that means he has also shrugged off the geopolitical niceties embraced by his predecessors. No other president has met with a then-minor opposition leader from a major ally the week after winning the presidency, and then repeatedly hosted him in the Oval Office, as Trump has done with UK Reform Party leader Nigel Farage. No other president has allowed a senior member of his administration to endorse a far right party in another major ally, or permitted his vice president to violate diplomatic protocol by meeting with the leader of said party, as Trump did with Elon Musk and Vice President JD Vance, respectively, concerning the Alternative for Germany.

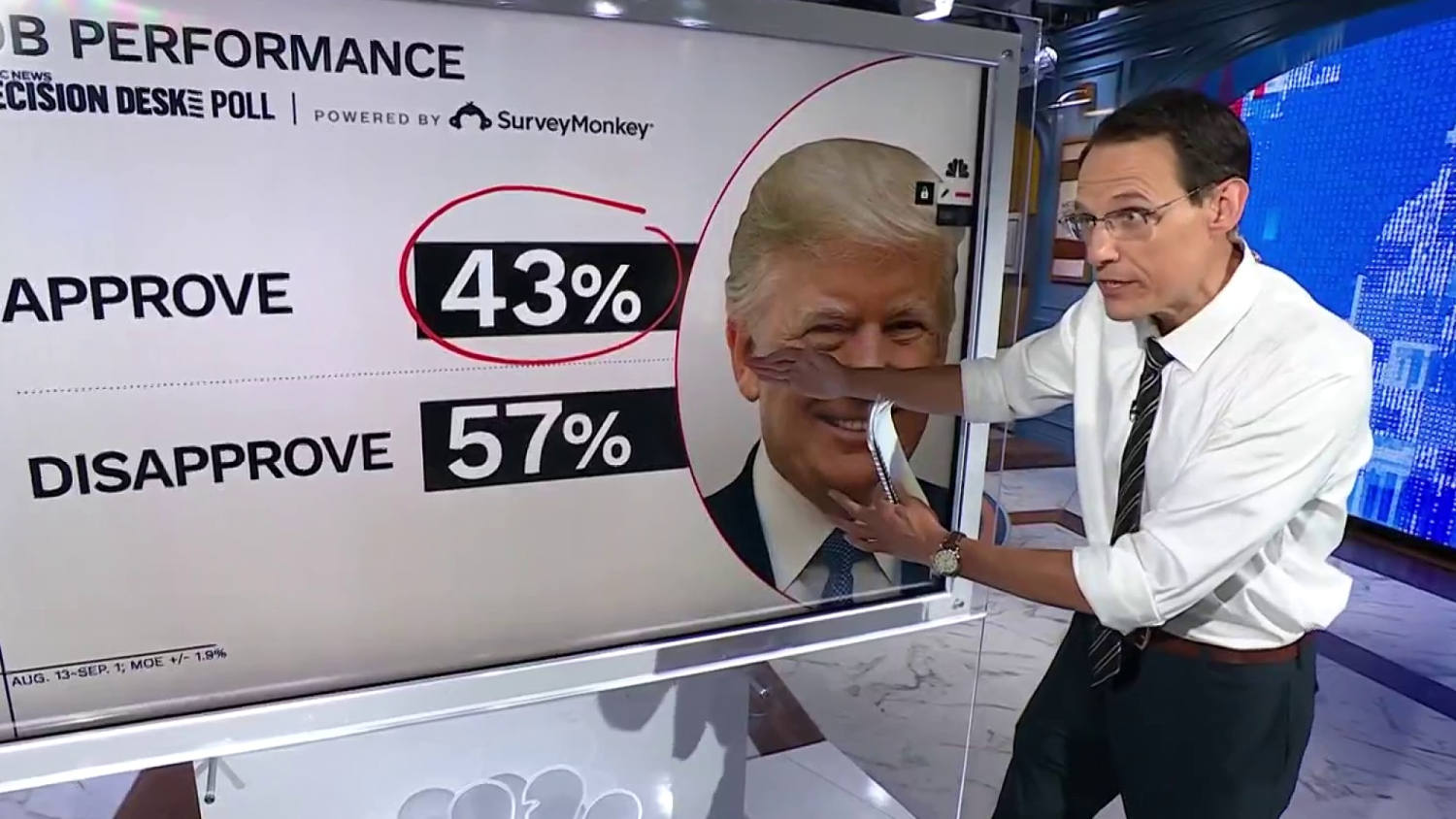

Kirk himself embodied a significant element of this transatlantic linkage. According to a recent NBC News poll, 47 percent of Gen Z men approve of Trump’s leadership, opposed to just 26 percent of women. This represents the largest gender gap of any age cohort. Populist nationalist parties in Germany, France and Spain all boast high levels of support from young men, Spain especially, where the populist nationalist Vox is the top choice for men under 25.

It's hard to recall a time when the American and European right were so much in lock-step. During the Cold War, conservative parties were united above all by anti-communism. What’s known as “globalization” had yet to take root, and so the cultural issues that have come to dominate contemporary politics — and effectuated the political realignment in Western countries — did not have the salience that they do today. Political parties in the United States were also more ideologically diverse (hard as it may be to imagine, there used to be such things as conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans), and in Europe, the dominance of the volksparteien (“people’s parties” like the German center-left Social Democrats and center-right Christian Democrats) attenuated political extremism by keeping it under a big tent. All of these factors diluted the power of ideology alone to determine the makeup of a broad political coalition and offered consistency in the way presidents and prime ministers of different political families worked with one another.

An exception to this tendency was the bond that developed between President Ronald Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s, the most consequential relationship between an American president and a European leader since Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. But while there was a strong ideological component to this link in the form of support for free market economics and high defense spending, it was heavily shaped by personality.

The relationship between the transatlantic left could also be so described. Europeans loved Barack Obama, who in 2008 made an unprecedented campaign stop in a foreign capital, Berlin. They have protested Trump when he visits their capitals. The death of George Floyd inspired outrage across the continent. But there was no programmatic follow-up to the European love affair with Obama, popular anger with Trump has not meaningfully affected the policies of national governments, and attempts to Europeanize Black Lives Matter and other American culture war fixations fizzled out. The last time there was any real substantive cooperation amongst the transatlantic left was during the heyday of the neoliberal “Third Way” in the 1990s and early 2000s, when Tony Blair’s New Labour, Gerhard Schroeder’s Social Democrats and Bill Clinton’s New Democrats embraced similar policies — deregulation, trimming the welfare state and getting tough on crime — to modernize left-wing politics for the 21st century. Liberal America used to point to Sweden as a progressive utopia; that’s a lot harder to do nowadays, what with its prevalence of immigrant gang warfare, grenade bombings and the use of teenage girls as “hitwomen.”

Until the concomitant rise of MAGA and MEGA, which are both defined by their grassroots appeal, transatlantic political cooperation was mostly an elite project. Tories and Christian Democrats would annually visit the GOP presidential convention while Labourites and social democrats crashed the Democratic one. Collaboration also took place outside the transatlantic space, far away from the attention of actual voters. Earnest democracy-builders at legacy Cold War institutions like the International Republican Institute (affiliated with the Republican Party) and the National Democratic Institute (affiliated with the Democrats) mentored fledgling democrats in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the former Soviet Union alongside colleagues from the Konrad-Adenauer Foundation (CDU) and the Friedrich Ebert Foundation (SPD). Internationalist to their core, these institutions have been gutted by the Trump administration, and their futures remain in doubt as America turns inward. Also gone is the expectation among allies that the foreign policy of the United States will maintain some basic level of consistency from administration to administration.

It's a paradox of our times that the political parties in the West cooperating most closely at the international level are nationalist forces pledging to close borders, withdraw from international institutions and oppose multiculturalism. Whether these parties will get along so swimmingly once they are in power is a question that has yet to be tested. Until that day, they stand united on the martyrdom of one young American man, a force of nature in life whose death may prove to be the catalyst for a global political awakening.

.png)

English (US)

English (US)